The Huacas de Moche Museum, also known as the Santiago Uceda Castillo Museum,

is a museum located in the department of La Libertad, Peru.

The Santiago Uceda Castillo Museum is a space dedicated to culture and is made

up of four main elements: (1) the exhibition halls, (2) the communal area, (3)

the research center and (4) the theater.

|

Entrance to the museum

This cultural space is not only a site museum for the exhibition of

objects found in archaeological excavations, but also a community

research and development center.

|

|

Figures for photos in traditional costumes

BThe figures are dressed in traditional costumes and behind them we can

see Cerro Blanco.

|

|

The depiction of nature

In Moche art it is possible to identify painted landscapes wich are

clearly those of marine, desert, river or lake environments. In

addition, animals from the sea, land or air are modeled or painted with

great attention to detail. Plants and animals are represented not only

because they form part of the Moche people's surroundings, but also

because they possess particular characteristics and attributes which

define them and give them their own symbolic significance, as in the

case of the San Pedro cactus, the sacred plant used by priests.

-

The dominant animals of the differert worlds, such as birds of prey,

big cats and reptiles, were deified. Those animals encountered at the

limits of different worlds - between the desert and the dry forests in

the case of foxes, the coast in the case of seabirds, and on rocky

shores and islets in the case of crabs - are common in Moche art.

These species are depicted in a realistic manner, as well as in their

anthropomorphized or supernatural versions.

|

|

Urban specialists and ritual objects

In the bustling city of Moche urban specialists resided who were

entrusted with a number of activities. Some of them were architects and

engineers, while others were distinguished painters. Other residents

included the highly-skilled pottery workers who made beautiful ceramics,

as well as skilled metalworkers and gold and silversmiths. Expert

weavers and the best cooks and chicha [corn beer] makers also resided in

the city, as did the strong porters responsible for bringing materials

and other objects from faraway places to the city.

-

Moche art depicts some of the activitles that were directly related to

ritual practices, such as the making of clothing for the great lords

or priests and the transporting of funerary offerings.

|

|

The ornaments of the priest-lords

For a long time priests were the leaders of Moche society. They

organized life in the city and the work of the craftspeople. In some

ceremonies or rituals, these priests would represent the principal Moche

gods and behave like them.

-

They would dress in special clothing, cover their faces with masks and

place adornments on their heads.

-

These adornments represented big cats such as the jaquar and ocelot,

birds like the condor or eagle, and reptiles, including snakes and

iguanas.

-

Their chests were covered with necklaces and breastplates made from

semiprecious stones and shells, and they wore bracelets on their

wrists.

-

Fine nose ornaments hung from their noses and the lobes of their ears

were pierced to accommodate large ear ornaments made from gold or

other materials which were inlaid and decorated with complex

iconography.

|

|

The principal deity

The principal god of the Moche pantheon is depicted with a frown and

wrinkles, while his mouth displays feline teeth.

-

He wears serpent ear ornaments and a belt which ends in the heads of

condors or serpents.

-

This sculptural ceramic bottle representing the head of the deity was

found in Tomb 4 of the Uhle Platform.

|

|

Ritual combat

Ritual combat marked the beginning of the most important sequence of

ceremonial events in Moche culture. This sequence began with combat

between lavishly dressed warriors who faced each other with clubs and

maces. The objective of this hand to hand fighting was to select the

victims for subsequent human sacrifices. Moche iconography shows how

this combat took place in desert areas, for in the painted scenes which

decorate pottery sand dunes and cacti can be seen in the surrounding

landscape.

-

The combat ended when one of the warriors was able to remove his

opponent's helmet and grab him by the hair. The defeated warriors were

then stripped. The clothing and weapons on the vanquished were carried

in a bundle which the victorious warriors would hang from their clubs.

-

The procession of victorious and defeated combatants was the climax of

the first stage of the ceremonial sequence, and it probably took place

in the great ceremonial plaza of the Huaca de la Luna. The sequence

would continue with the preparation of the captive warriors fot their

sacrifice.

|

|

Combat weapons

-

Left: Anthropomorphic club. Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 2, tourist inn,

urban center.

-

Center: Helmet with serpents. Moche ceramic bottle. Uhle Platform,

Huaca de le Luna.

- Right: Mace and shield. Moche ceramic bottle. Urban center.

|

|

Warriors

-

Left: Watchtower warrior. Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 24, Uhle

Platform, Huaca de le Luna.

-

Center: Combat between humans and supernatural beings. Moche ceramic

bowl with open walls. Uhle Platform, Huaca de le Luna.

-

Right: Warrior. Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 2, Plaza 3C, Huaca de la

Luna.

|

|

The sea lion hunt

In tombs excavated at the Huaca de la Luna pottery items depicting sea

lions have been found. In Moche iconography we can see scenes

representing the hunting of sea lions. In these scenes altars or small

temples can be distinguished which were probably located on the islands

where sea lions hunts took place.

-

Sea lions behave in a particular way during times of environmental

changes such as those caused by the El Niño phenomenon. On these

occasions, sea lions fiercely attack the nets of fishermen in search

of food, which is less abundant as a result of an increase in ocean

temperatures. The sea lions therefore become an enemy of the fishermen

and they must be defeated in order to appease the divine fury of the

gods. In this way the sea lion hunt would have been associated with

ritual combat. The hunters would carry maces similar to those used

during ritual battles and the sacrifice ceremonies.

|

|

Ritual races

A number of ritual races have been depicted in Moche art. In some races

the participants carry in their hands bags containing lima beans,

together with sticks or thin reeds, which were presented to the gods at

the end of the competition. These races probably formed part of the

initiation ceremonies which marked the passage from adolescence to

adulthood. Young men would compete in these races to demonstrate their

skill, strength and physical stamina. In Moche iconography we can see

how these young men wore elaborate headdresses decorated at the front

with large discs or trapezoidal plaques. In the urban zone of the

archaeological complex a number of tombs of individuals have been found

containing copper discs similar to those worn by the runners.

-

In other racing scenes, the participants do not carry sticks or bags

of beans, and their headdresses are similar to those worn by warriors.

These races are not competitions and they do not form part of the

initiation rites, but are instead associated with ritual combat.

|

|

The sacrifice ceremony

-

Clubs were the weapons used by warriors in ritual combat. Some Moche

altars associated with the sacrifices that were performed after combat

were decorated with ceramic club heads.

-

The ritual combat culminated in the offering of the blood of the

defeated warriors to the principal gods of the Moche pantheon.

-

The step motifs which appear in ritual and mythological scenes

depicted in Moche art serve to link the world of mankind with the

upper world iahabited by the gods.

-

The defeated warriors were presented as the vessels containing the

blood which would be offered to their gods.

-

The priests who performed the sacrifices of the captive warriors were

represented as anthropomorphic feline creatures and foxes.

|

|

The deer hunt

One of the ceremonial activities most frequently depicted in Moche art

is the "Deer Hunt”. The hunting of agile white-tailed deer, a native

species of Peru's northern coast, was depicted in the fine line drawings

or relief scenes used to decorate pottery.

-

The hunters are Moche lords dressed in very elaborate headdresses,

adorned with feathers and metal, large ear ornaments and breastplates.

They carry clubs, lances, darts and spear-throwers, and they use nets

to trap the deer before its eventual capture.

-

The clothing worn by these noble hunters is very similar to that used

by Moche warriors. The deer, in its anthropomorphized version, is

depicted in Moche art as a warrior prepared for combat, defeat or

captivity. For this reason, some researchers believe that ritual

combat and the ceremonial hunting of deer were symbolically

associated. The objective during both ritual combat and deer hunting

would have been to capture the opponent for sacriliea.

|

|

The ceremonies

At the Huaca de la Luna the most important rites associated with Moche

religion were performed. The ritual calendar was intimately related to

the development of agricultural activity throughout the year. It was

necessary to perform ceremonies in order to establish and ensure both

political and cosmic order. However, events occurred which broke or

disturbed this order, such as the climatic variations caused by the El

Niño phenomenon, or a powerful earthquake. In these circumstances rites,

offerings and sacrifices of different kinds were required to calm the

anger of the gods. If these petitions were answered, then it would be

necessary to thank the principal divinity. For the Moche, the best way

to do this was to offer the blood and lives of their own people.

-

At the Huaca de la Luna evidence has been found of a series of

ceremonies which probably constituted the focal point of Moche

religion, and which culminated with the Sacrifice Ceremony. This

ceremonial sequence began with the ritual combat which would decide

who would be offered in sacrifice. This was followed by a procession

of the victorious and defeated warriors. The defeated warriors were

presented as prisoners; stripped of their clothing and weapons they

were led naked to the high priests. The captives were then prepared

and instructed through the preparation and making of offerings.

Subsequently, they were sacrificed and their blood was extracted. This

process culminated with the presentation of a cup containing the blood

of the sacrificed to the principal gods, together with an act of

fertilization. This ritual was not attended by the nasses, and it was

performed in areas of the temple to which access was restricted.

|

|

Procession of warriors with ceremonial attire and weapons

Tomb 44. Plaza 2B, Huaca de la Luna.

- Step 1 of the main facade.

|

|

Procession of victorious and defeated warriors after ritual combat

Tomb 19. Plaza 2B, Huaca de la Luna.

- Step 1 of the main facade.

|

|

Predatory spider with trophy head

Tomb 22. Plaza 2B, Huaca de la Luna.

- Step 3 of the main facade.

|

|

Feline deity with fish offerings

Tomb 2. Platform II, Huaca de la Luna.

- Step 4 of the main facade.

|

|

Two-headed feline-iguana deity holding a trophy head

Tomb 7, Architectural complex 35, Urban center.

- Step 5 of the main facade.

|

|

Reliefs in the principal facade of the Main Temple

In the many steps of the facade of the Main Temple, at the foot of the

large ceremonial patio, polychrome mud reliefs were produced depicting

motifs and scenes associated with ritual combat and human sacrifices. It

is likely that mass rituats were performed in this area.

-

The iconography also seen on the facades of the earlier buildings,

following the same architectural pattern, distributes individuals

arranged from the bottom to the top of the steps, with the aim of

locating the principal deity at the highest part of the facade.

-

Other areas of the temple, such as the patios located in the upper

part of the main platform, or the walls adjacent to the Main Altar,

were also lavishly decorated.

-

In pieces of pottery found during a number of excavations at the Huaca

de la Luna, the same motifs seen in these reliefs can be

distinguished.

|

|

The temples is the mountain

Moche pottery often features depictions of hills inhabited by deities

and mythological beings.

-

This pottery bottle is decorated with the figure of a monkey, and in

the lower part a small figure of the main deity can be seen,

incorporated into a mountain.

|

|

The evidence of sacrifices

The discoveries at the Huaca de la Luna have shown that the Moche

practiced two forms of human sacrifice: one which was related to the

presence of some kind of El Niño event; and another associated with

regular climatic conditions. The former ritual was probably intended to

restore order, while the latter was meant to maintain order.

-

In each case, the treatment of the bodies of the dead was different.

The marks found on the bones of those who were sacrificed during

periods of intense rainfall indicate that they suffered blows to the

head administered with clubs; some had their throats cut, while others

were cut into pieces. Finally, their bodies were left exposed on the

mud formed by the rains.

-

The bones of those who were sacrificed at other times show signs of

having had their throats cut, after which their flesh was stripped

from their bones. In this case, the bodies were placed in graves near

the site where the sacrifices took place. A number of bones show signs

of cuts and blows. In-depth analysis of this evidence has given us an

understanding of the details of the ceremonies surrounding the

practice of human sacrifice in Moche society.

|

|

Moche shaman

Tomb 10, Platform I.

-

This tomb was excavated in 1997 in the eastern sector of the main

platform of the Huaca de la Luna. The tomb had already been sacked and

only fragments of bone belonging to an adult were found.

-

In the disturbed landfill pieces of pottery from Moche IV were found.

One of them is a bell-shaped cup, the inner walls of which have been

painted with serpents with feline heads. The sculptural bottle depicts

a priest sitting with his legs crossed and wearing a headdress with

lateral appendages, ear ornaments and a necklace made from inlaid

shells and natural slate. In one hand he is holding an object, similar

to one used by modern shamans in the Northern Coast of Peru.

|

|

Moche reburial

Tomb 3-4, Platform I.

-

This tomb was built in a landfill during the final phase of the

construction of the Huaca de la Luna. When this tomb was excavated in

1993, the skeleton of a buried man was found who had been between 40

and 45 years old when he died. The skeleton was not articulated, and

this fact would seem to indicate that during the Moche period the

already fully decomposed body was disinterred from its initial place

of rest and reburied in this tomb, thereby producing the disordering

of the bones. The deceased may have been a priest or important leader

during the earlier stages of Moche society, who had to be reburied at

this site. This interpretation is reinforced by the fact that the main

ceramic offerings found belong to an earlier pottery style associated

with the previous phases of the construction of the temple.

-

In this tomb pieces of pottery were arranged in pairs, including

pitchers representing lizards and others representing individuals who

officiated at ceremonies. This pattern in the arrangement of the

funerary offerings is related to the concept of duality that lay

behind the organization of Moche religion and their beliefs regarding

life after death. One of the pottery artifacts represents the head of

a seal; according to Moche beliefs, the hunting of this animal can be

seen as a counterpart to the ritual combat leading to human sacrifice.

|

|

Moche warrior-priest

Tomb 1, Platform I.

-

This tomb, discovered in 1991 on the main platform of the Huaca de la

Luna, was the burial place of an officiating priest of the Moche

religious cult who probably held a mid-level rank and who had warrior

functions. He was between 20 and 35 years-old when he died. He was a

tall individual for the standards of the time (168 cm, 5.5 ft). He

suffered fractures to some of the bones of his right foot and his

collarbones indicate that he may have suffered from acute

tuberculosis. His death may have been caused by this chronic disease.

-

Funerary offerings composed of ten pottery items were arranged inside

and around his coffin. Of these, two sculptural bottles are of a

particularly high quality, and they depict a warrior and a musician.

The warrior is wearing a headdress composed of two elements in the

shape of club heads and he is carrying a shield and club. The musician

is a flautist and he is wearing a necklace, ear ornaments and

bracelets, adornments which indicate that he enjoyed a certain rank

within the social hierarchy. The details of his adornments are made

from inlaid natural slate.

|

|

The lord of the prisoners

Tomb 4, Uhle Platform.

-

This chamber tomb with niches was excavated in 2000 on the Uhle

Platform, to the west of the main platform of the Huaca de la Luna. A

man aged between 35 and 45 was buried in this tomb. The tomb was

partially disturbed in ancient times, apparently as part of a Moche

ritual. The cranium was removed, together with one of the individual's

upper limbs when the body was already partially decomposed.

-

The funerary offering was composed of fired and unfired pottery

vessels pieces. There are several pairs of pieces which share the same

theme, including those which represent prisoners, feline heads, scenes

depicting the dance of the dead and a larger series of identical

pitchers. The depicted themes are related to the capture of prisoners.

Necklaces and beads were also found, together with a fragment of

animal bone carved with the figure of a Moche warrior, surrounded by

clubs.

|

|

Blind man with tattoos

This fine sculptural bottle formed part of the funerary offerings of

Tomb 32 of Patio 2, excavated in the southeastern sector of the Huaca de

la Luna. It represents a priest sitting in an attitude of prayer. The

body of the man is covered by a painted red tunic and he is wearing a

necklace made from plaques. He is clasping his hands together in front

of him. The head is covered with a headdress decorated with S-shaped

designs and an adornment in the form of the head of a club. His face is

covered with incised designs of felines, an iguana, birds, foxes and

fish; a vulva and a phallus can be seen below his jaw.

|

|

Ancestors

The Moche believed in an “underground world” which was inhabited by

their deceased after they had left this life and passed through the

process of death. The dead are depicted interacting with the living, and

also in ceremonies, in which they can be seen dancing and playing

musical instruments.

-

Some of the dead would have been carefully and rigorously prepared and

treated in accordance with certain rituals in order to ensure their

conversion into “ancestors”. These individuals were usually great

lords who because they had fulfilled important roles in life would

occupy a special place in the next world. In order to propitiate this

transformation, complex funerary rites were practiced.

|

|

Body artifact representing feline

Platform I, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

The blind priest

Tomb 32, Plaza 2B.

-

This tomb was excavated in 2000 to the southeast of the Huaca de la

Luna. It was a shaft tomb and it had four niches, of which three had

been affected by sacking and only one was discovered intact.

-

The tomb belongs to the earty phases of Mocke culture. It contained

fragments of metal and pottery vessets, among which stirrup handle

bottles, pitchers and bowls were found. Two of the bottles are

notable: one represents a man that carries offerings, and the other a

blind priest with scars. Among the pieces of pottery found in this

tomb there is frequent use of the stepped iconographic motif,

accomparied by the scroll design.

|

|

The Moche weaver

Tomb 8, Platform I.

-

This tomb was excavated in 1995, in the central sector of the main

platform of the Huaca de la Luna. This chamber tomb was built using

mud bricks to line the structure. The reed coffin placed in the

interior of the tomb contained an adult woman of between 50 and 60

years of age who was approximately 155 cm (5 ft) tall.

-

Metal plaques were placed on her head, hands and feet. Her funerary

offerings included gourds containing the remains of camelids, and

pottery vessels. In addition, spindle-whorls were found, all of which

were painted black and decorated with cream-colored painted incisions.

|

|

Chimu adornments

Around the year 800 CE, after the crisis experienced among the Moche

priesthood and the subsequent decline in the political power of the

ruling elite, the city and the temple were abandoned.

-

Several hundred years later, Chimu lords and priests were buried at

the Huaca de la Luna, for the site had not lost its sacred character.

-

In some of these important tombs Spondylus shell bracelets and

breastplates were found, as well as ceremonial cups and models

depicting the funerary processions and ceremonies of the Chimu lords.

|

|

Chimu ceremonial scenes

These sculpted scenes made from wood and reed were found in Chimu tombs

excavated in 1995 in the landfill that once covered the Old Temple of

the Huaca de la Luna. These tombs had already been sacked during the

colonial period by those in search of precious metals.

-

Together wit fragments of textiles, seeds, seashells and feathers, a

beautiful litter made from copper and reeds and covered with cotton

was discovered. In addition, rxcavations unearthed a wooden

architectural model of a ceremonial plaza, with 26 figures and 5 reed

platforms covered with cloth, with figures carved from wood inlaid

with seashells depicting a funeral procession, human sacrifices and

the presentation of offerings.

|

|

Ornaments of ceremonial clothing

A number of objects made from gold were found in the basket offering

discovered on the main platform of the Huaca de la Luna. These objects

were part of the ceremonial clothing worn by the great lords who

presided over the ceremonies that were held in the temple complex.

-

Some of these metal ornaments are the step designs and feather crests

which adorned the headdresses worn by Moche lords and priests. The

gold discs were sawn to the helmets of warriors. They represented ear

ornaments, which were some of the most important ceremonial

adornments, for they indicated the status and role of the wearer

within the Moche hierarchy. These discs are decorated with

iconographic motifs that can also be seen in the friezes and murals of

the Huaca de la Luna, such as the serpent and warrior.

-

Moche lords and priests would decorate themselves with ornaments made

from gold, silver, gilded copper and silvered copper. In this way they

presented themselves before the rest of the population as supernatural

beings, gleaming like the sun, moon and stars. To achieve this effect,

different shaped metal plaques featuring a variety of designs were

sewn onto their shirts and tunics.

-

On the main platform of the Huaca de la Luna an offering was found

which consisted of a basket containing textiles and repoussé gold

sheets. Several of this metal objects were flaps which were sewn onto

clothing and would have emitted jingling sounds when the wearer moved.

|

|

Coca leaf ceremony

This scene depicting the chewing of coca leaves is illustrating one of

the most important Moche ceremonies. Coca seeds have been found in Patio

2 of the Huaca de la Luna. It is likely that this open area was used for

the consumption of coca leafs in acts which would have been related to

the propitiatory and premonitory rites designed to ensure fertility and

an abundant supply of water.

-

The Mochce priests are gathered under an archway formed by a

two-headed serpent. They are sitting and they are carrying bags

containing coca leafs. They are also holding containers used to hold

the lime which they mixed with the coca in order to accelerate the

biochemical reaction when the leaves were chewed. In the ritual scene

painted on a piece of pottery, the large dark circles represent heavy

rainfall.

-

The gold lime holder was found in Tomb 2 of the main platform,

indicating that the individual buried in that tomb may have been one

of the priests who participated in the coca leaf ceremony.

|

|

Coca leaf chewers

These sculptural pottery faces have been interpreted as priests chewing

coca leaves. The commonly shared characteristic of these pieces is their

prominent cheeks. This is a typical characteristic of those persons who

chew coca leaves and store the coca in their cheek while the leaves

release the alkaloids they contain with the help of small quantities of

lime ingested as a catalyst.

-

These pieces may depict priests who ingested substances that enabled

them to enter into a trance-like state and acquire the power of

experiencing visions and making contact with the celestial world and

the world of the dead. Three of these pieces are stirrup handle

bottles, while one is a sculptural vessel and another is a perfectly

anatomical mask which may have been used in ceremonies associated with

the chewing of coca leaves.

|

|

Serpents

The serpent is an animal which moves through different worlds and

enables communication between them.

-

In pre-Columbian art the two-headed serpent with feline features has

also been interpreted as the arch which supports the Milky Way.

-

The attributes of felines and foxes, together with those of a bird of

prey, are combined in some hybrid beings based on the body of a

serpent.

-

The frequent depiction of the serpent may be explained as the symbol

of rivers, fertility and water.

-

In Quechua this gigantic serpent with feline features which moved

through different worlds was known as amaru.

|

|

Simple bottle with side handle, globular body and annular base

Period: Early Intermediate.

-

Reduction cooking vessel. The neck has cream-colored paint. The handle

is painted dark red. 3/4 of the body is covered by a layer of cream

paint. The rest of the body and the entire base have been painted dark

red.

-

It has "repair" at the handle-neck joint. In the cream area of the

body there is a scene of two anthropomorphic characters standing, they

are facing each other. Each character wears a half-moon-shaped

headdress with a plume and feathers, from the same headdress parallel

bands emerge like braids, decorated with triangles and horizontal

lines. They have paint on their face, hands and feet.

|

|

The sacred mountain

Cerro Blanco, also known as Alec Pong, or "sacred stone", dominates the

landscape around the complex with its magestic and imposing pyramidal

form. This natural landmark was considered a protector god by the Moche.

It was in relation to this hill and the Moche river which connected them

with the sea that the urban space of this society was organized. The

mountain was a god, and it was from this tectonic force that water

emerged and flowed. This identity with which the mountain was attributed

can be seen clearly in a number of objects: the Decapitator God is also

the God of the Mountains and one of his essential attributes is the

serpent form, symbolizing the river.

|

|

God of the mountains

Moche ceramic jug. Tomb 17, Platform I, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

God of the mountains

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 10, Architectural complex 35, Urban center.

|

|

God of the mountains

Moche ceramic jug. Tomb 17, Platform I, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

Chimu offerings with Wari influence

After the collapse of the Moche state, the city and the Huaca de la Luna

were abandoned. However, during the Chimu period some parts of the

architectural complex were reused. In the urban nucleus, the ground was

leveled and used for growing crops. At the Huaca de la Luna altars were

built, offerings were made and high-ranking individuals were buried, all

of which indicates that this important Moche temple retained its sacred

character in spite of the passage of time.

-

This pieces form part of the offerings found in a Chimu burial located

in the main plaza of the Huaca de la Luna. The style and decoration of

these pieces correspond to the early Chimu period, with clear Wari

influence.

|

|

Statues of the sacrificed

On the ceremonial platform adjacent to Platform II, 70 bodies of

sacrificed warriors were found.

-

Together with this remains, almost 50 clay statues depicting naked

prisioners with ropes tied around their necks were discovered. These

statues are approximately 60 cm (24 in) tall, and they represent

captive warriors. Their bodies are decorated with complex designs. On

one of their faces motifs can be seen which have been interpreted as

the chrysalises of the insects that appear on decomposing bodies.

-

According to Andean religious beliefs part of the essence of the dead

takes the form of flies after death.

|

|

Ceremonial knives

Tumis, or ceremonial knives, were used during sacrifices.

|

|

The Moche world

At first sight it may appear that Moche artists depicted their

surroundings in a naturalistic manner in their murals, friezes, pottery

and objects made from metal, wood or bone. However, for the Moche these

art objects were a means of communication and an expression of their

world view and religious beliefs.

-

In the Moche world humans coexisted with the dead and the gods. In

their art they represented these relationships and interactions in

great detail. In the ocean, for example, there lived marine demons as

well as fish. Both human beings and the gods fished in these waters

and faced monsters and divine creatures.

-

The Moche people’s fields provided harvests because the gods had

fertilized the earth and because irrigation was practiced in

accordance with the demands of certain rituals.

|

|

Priest with fangs

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 19, Plaza 28, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

Ai Apaec in sexual intercorse with woman

Moche ceramic jug. Urban center.

|

|

Sea deity fishing

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 8, Uhle platform, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

Ai Apaec capturing a bird

Moche ceramic jug. Tomb 10, Architectural complex 35, Urban center.

|

|

Sea demon with decapitated heads

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 8, Platform I, Huaca de la Luna.

|

|

Combat between Ai Apaec and deer

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 10, Architectural complex 35, Urban center.

|

|

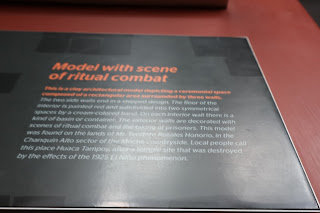

Model with scene of ritual combat

This is a clay architectural model depicting a ceremonial space composed

of a rectangular area surrounded by three walls.

- The two side walls end in a stepped design.

-

The floor of the interior is painted red and subdivided into two

symmetrical spaces by a cream-colored band.

- On each interior wall there is a kind of basin or container.

-

The exterior walls are decorated with scenes of ritual combat and the

taking of prisioners.

-

This model was found on the lands of Mr. Teodoro Rosales Honorio, in

the Chanquin Alto sector of the Moche countryside. Local people call

this place Huaca Tampoy, after a temple site that was destroyed by the

effects of the 1925 El Niño phenomenon.

|

|

Tombs of the urban zone

The tombs of individuals who were probably mid-ranking members of Mocha

society have been found in the architectural complexes of the urban

zone.

-

All of the pieces of pottery that formed part of the funerary

offerings discovered were clearly associated with Moche religious

beliefs and ritual practices related to those beliefs.

-

These include: recipients used when eating ritual foods;

representations of nonkeys, an animal with a resemblance to cadaverous

human bodies which was also symbolically associated with warm and

hunid forest regions; mutilated or dead individuals; and the shamans

or priests who presided over different ceremonies, such as the

preparation of bodies for burial.

|

|

Feline

Moche ceramic canchero. Tomb 1, Architectural complex 8, Urban center.

|

|

Dead man playing drum

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 7, Architectural complex 25, Urban center.

|

|

Shaman

Moche ceramic jug. Tomb 7, Architectural complex 35, Urban center.

|

|

Monkey carrying offerings

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 1, Architectural complex 36, Urban center.

|

|

Deformed face

Moche ceramic bottle. Tomb 2, Architectural complex 25, Urban center.

|

See also

Source

Location