Huaca de la Luna ("Temple or Shrine of the Moon") is a large adobe brick structure built mainly by the Moche people of northern Peru.

Along with the Huaca del Sol, the Huaca de la Luna is part of Huacas de Moche, which is the remains of an ancient Moche capital city called Cerro Blanco, by the volcanic peak of the same name.

|

Approaching the Huaca de la Luna accompanied by a running dog |

|

The ancient city of Huacas de Moche

|

|

Agricultural engineering

|

|

Huaca de la Luna Plan

|

|

Panorama of the entrance (Plan No. 1) |

|

Welcome mural painting (Plan No. 2) |

|

Moche urban center (Plan No. 3) |

|

Panorama of Huaca de la Luna from northwest

|

Patio of the Serpents (Plan No. 4)

|

The Patio of the Serpents |

|

The Fight of the Deities

|

|

Panorama of Huaca de la Luna from northwest |

The Patio of the Ocelots and the Sea Deamon (Plan No. 5)

|

The Patio of the Ocelots and the Sea Deamon

|

|

Panorama of the Previous building, Second fase |

|

Last building |

|

The Enclosure and Altar of the Sea Deamon

|

|

Enclosure and Altar of the Sea Deamon |

|

Panorama of the Enclosure and Altar of the Sea Deamon |

|

The Two Superimposed Murals

|

|

First fase mural |

|

Panorama of Priests holding each othe hands, as if dancing |

Old Temple

|

The Great Patio and the North Facade of the Old Temple

|

|

Panorama of the Great Patio (Plan No. 6) |

|

Panorama of the North Facade (Plan No. 7) |

|

North Facade: Lower Terrace Murals

|

|

Panorama of the Lower Terrace Murals |

|

Lower Terrace Mural Details |

|

North Facade: Mid-level Terrace Murals

|

|

North Facade: Upper Terrace Murals

|

|

Superimposition of the Old Temple Facades |

|

Detail of the North Facade |

|

Corner enclosure and the Mural of the Myths (Plan No. 7) |

|

The Mural of the Myths |

|

Going up the ramp to the upper floor |

|

Cerro Blanco seen from the upper floor |

|

Panorama from the upper floor |

|

The Sacrificial Enclosures |

|

Panorama of the Sacrificial Enclosures (Plan No. 8) |

|

Going up to the Great Altar |

|

Rooms Behind the Great Altar |

|

Panorama of the Rooms Behind the Great Altar (Plan No. 9) |

|

The Great Altar |

|

Architectural and Pictorial Changes of the Great Altar

|

|

Panorama of the Great Altar (Plan Np. 10) |

|

Wall next to the Great Altar |

|

Steps of the Great Altar |

|

Panorama of the upper floor seen from the Great Altar |

|

The City of Huacas de Moche |

|

Panorama of the view to the northwest |

|

Panorama of the Atrium (Plan No. 11) |

|

Going down to the Patio of the Rhombuses |

|

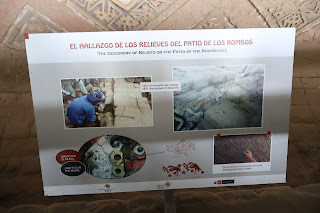

The Discovery of Reliefs on the Patio of the Rhombuses |

|

The Patio of the Rhombuses |

|

Location of the Patio of the Rhombi in the Temple |

|

Panorama of the Patio of the Rhombuses (Plan No. 12) |

|

The Ceremonial Enclosure of the Previous Patio

|

|

Ceremonial Enclosure of the Previous Patio |

|

The Ceremonial Enclosure

|

|

The Ceremonial Enclosure |

|

The Murals of the Superimposed Patios |

|

Panorama of the Murals of the Superimposed Patios |

|

The image of the God of the Mountains |

|

The Tomb of the Priest |

|

The Tomb of the Priest |

|

The Sacrifice Area of 600 CE |

|

Penorama of the Sacrifice Area of 600 CE (Plan No. 13) |

|

Sacrifice Area of 600 CE and Cerro Blanco |

|

Aiapaec, the God of the Mountain.

|

See also

Source

Location