The Cao Museum is a Peruvian museum located in the district of Magdalena de

Cao, in the province of Ascope, in the department of La Libertad.

The Cao Museum is part of the El Brujo archaeological complex and is made up

of 7 rooms that cover a large part of Moche history.

|

El Brujo Archeological Complex

The site is situated above an extensive geological terrace, 6 meters

above the surrounding agricultural area. Starting 5,000 years ago and

continuing into the present, the land around the archeological complex

has been systematically cultivated.

-

The ancient peoples that inhabited this area inherited and modified

the irrigation techniques of their ancestors, and toward the strat of

the current era, more sophisticated irrigation systems gave rise to

large-scale agricultural irrigation. As the principal component of the

North Coast economy, agriculture favored and gave impulse to the

development of ever more complex societies and systems of political

power.

-

The Moche (200-800 CE) extended their domain throughout the Chicama

river valley and dominated the middle and lower sections of the rivers

of the North Const all the way to where they met the sea. Using an

extraordinary network of canals and aqueducts, the Moche began their

true conquest and expansion over the desert.

|

1400 years of history room

In this room the focus falls on the processes of change and continuity

manifested both in the ceramic technique and in the treatment of other

materials. The objects are organized within a chronological framework of 14000

years, a period that corresponds to the history of cultural occupation in El

Brujo.

|

Pyrographed gourd

Preceramic (3000 - 2000 BCE).

- Replica of the pyrographed gourd discovered at Huaca Prieta.

|

|

Pyrographed gourd with a lima bean design

Moche (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Pyrographed gourd with lid and geometric designs

Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE).

|

|

Pyrographed gourd showing stylized birds

Chimu (1200 - 1470 CE).

|

|

Pyrographed gourd with fish motifs

Chimu (1200 - 1470 CE).

|

|

Gourd with stylized incisions

Colonial (1532 - 1750 CE).

|

|

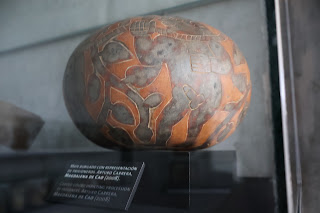

Pyrographed gourd depicting procession of prisoners

Arturo Carrera. Magdalena de Cao (2008).

|

|

Main ceramic shapes

Top: Principle ceramic forms at El Brujo complex

- Jar

- Pot

- Bottle

- Face-neck jar

- Sculpted stirrup-spout bottle

- Ribbon-handle bottle

Bottom: Stirrup spout shapes during the five Moche phases

|

|

Triangular incisions and owl

- Left: Triangular incisions. Cupusnique (800 - 500 BCE).

-

Right: Sculpted depiction of an owl. Gallinazo (200 BCE - 200 CE).

|

|

Triangular incisions

Cupusnique (800 - 500 BCE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of an owl

Gallinazo (200 BCE - 200 CE).

|

|

Owl and octupus

- Left: Sculpted depiction of an owl. Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

-

Right: Depiction of an octopus with tentacles in relief. Moche I (200

- 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of an owl

Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Depiction of an octopus with tentacles in relief

Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Toad and llama

- Left: Sculpted depiction of a toad. Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

- Right: Sculpted depiction of a llama. Moche II (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of a toad

Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of a llama

Moche II (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Shamanic scene and puma

- Left: Depiction of a shamanic scene. Moche IV (200 - 800 CE).

- Right: Sculpted depiction of a puma. Moche III (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Depiction of a shamanic scene

Moche IV (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of a puma

Moche III (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Geometric designs and figure

- Left: Geometric designs. Moche V (200 - 800 CE).

-

Right: Depiction of a figure and Spondylus. Transitional (800 - 900

CE).

|

|

Geometric designs

Moche V (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Depiction of a figure and Spondylus

Transitional (800 - 900 CE).

|

|

Geometric designs and fish

- Left: Geometric designs. Lambayeque V (900 - 1200 CE).

- Right: Sculpted depiction of a fish. Chimu (1200 - 1470 CE).

|

|

Geometric designs

Lambayeque V (900 - 1200 CE).

|

|

Sculpted depiction of a fish

Chimu (1200 - 1470 CE).

|

|

Grid design and cup

- Left: Grid design. Chimu-Inca (1470 - 1532 CE).

- Right: Ceremonial cup. Colonial (1532 - 1750 CE).

|

|

Grid design

Chimu-Inca (1470 - 1532 CE).

|

|

Ceremonial cup

Colonial (1532 - 1750 CE).

|

|

Jug and monkey

- Left: Sculpted jug. Cupusnique (800 - 500 BCE).

-

Right: Sculpted representation of a monkey. Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted representation of a monkey

Moche I (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted vessel depicting sea lion

Moche IV (200 - 800 CE).

|

|

Sculpted figure

Transitional (800 - 900 CE).

|

|

Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representation

Transitional (800 - 900 CE).

|

|

Dual representation of Naylamp

Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE).

|

|

Depiction of the god Naylamp

Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE).

|

|

Zoomorphic and geometric incisions

Chimu (1200 - 1470 CE).

|

|

Depiction of pelicans and fish

Inca (1470 - 1532 CE).

|

Cosmos architecture room

This room presents the sacred space as it was built and perceived by the Moche

inhabitants. The approach corresponds to the most important ceremonial

structure of the Sorcerer, the Huaca Cao Viejo, and with it the ritual

behaviors (i.e. burial of the temple and offerings) through which the space

acquired a sacred value. In this room you will find objects that have been

offered to the building and an infographic that shows the different

construction phases of the ceremonial center, presenting complex technical and

symbolic processes behind the construction of the truncated pyramids of the

Moche.

|

The Temple's Offerings

This room principally displays the offerings placed in the fill layer

that covered the temples. They consist of ritual objects that must have

ensured the “regeneration” of the sacred space.

-

As can be seen, in this case the Moche concepts of death and

regeneration were also applied to the architecture.

|

|

Wooden sculpture or “IDOL”

Moche (200 - 400 CE).

-

Wooden sculpture or “IDOL” with golden copper appliqués and attire.

-

It was placed as an offering on the ramped platform near the Lady of

Cao’s tomb.

|

|

“IDOL”

Moche (200 - 400 CE).

-

Placed as an offering under the adobe fill that covered the second

temple at Huaca Cao Viejo.

|

|

"IDOL"

Sculpture carved from lucuma tree trunk with representation of figure

wearing tunic and loincloth.

-

On the upper section, two crouching felines embody the mythical lunar

animal.

|

|

Spear throwers

Moche (200 - 400 CE).

-

Spear throwers with depictions of a pelicans, a catfish, and the lunar

animal.

- Carved from wood with shell and turquoise incrustations.

- Placed as offerings during the burial of the second temple.

|

|

Carved wooden eagle head

Moche (200 - 400 CE).

-

The cavity in the lower section suggests that it was placed on the tip

of a pole as a standard.

-

The residues of resin and feathers suggest that it had shell

incrustations in the eyes and was covered in colorful plumage.

-

This piece was also offered during the burial of the second temple.

|

The blood of the mountains room

Standing out against other ethnic groups in the Andean cultural area, the

Moche openly and publicly celebrated the ceremonial blood. The stages that

made up the ritual sequence of human sacrifice, also presented in this room,

were carefully described and narrated by the Moche artists, who through the

power of their images instructed and revealed to the masses the sacred code of

a warrior discipline. Although we do not fully know what was the meaning or

the nature of the armed encounter between the Moche, we know that the

objective of these great meetings exceeded a political ambition of an

expansive and military nature. Dense sacred substance, blood was the axis and

main component of the political and religious ideology of the Moche. In the

ritual imaginary, the captured warrior’s blood flowed down the mountain tops

like a turbulent and mighty river, and charged by the power and vigor of the

warrior, encouraged the rivers and fertilized the pampas. The ritual battles

and the consequent ceremony of sacrifice spread and practiced in all valleys

and centers of Moche power, demonstrating that blood, rather than a symbol of

conflict, was the paradigmatic symbol of integration between men and their

gods.

|

The Blood of the Mountains

Unlike other ethnic groups in the Andean cultural area, the Moche

celebrated the blood ceremony openly and publicly.

-

The stages comprising the ritual sequence of armed encounters were

carefully described and narrated by Moche artists, through their

images, instructed the masses and revealed to them the sacred code of

warrior discipline and the sacrificial rituals.

-

On ceramics and modeled clay remain inscribed the rumors of war, the

activities of an animated world used to secure power and resources

over the bloodied dust of conflict and oppositions among men.

-

The dense sacred substance, blood, constituted the axis and principal

component of the political and religious ideology of the Moche. In

ritual imagery, the blood of the captured warrior flowed down from the

mountaintops like a turbulent and overflowing river and, charged with

the power and vigor of the warrior, ran through the channels of the

desert.

-

Ritual combat and the consequent sacrificial ceremony spread and were

practiced in all the valleys and centers of Moche power, demonstrating

that blood, rather than a terrifying manifestation of crisis, was

actually the highest symbol of regeneration and the communication

between humans and their gods.

|

|

A mountain and the god Aia Apaec

Moche (600 - 800 CE).

-

Sculpted ceramic with representation of a mountain and an image of the

god Aia Apaec, also known as the “Mountain sacrifice” theme.

|

|

Cup and dog

-

Ceramic cup found in the tomb of a moche woman. Moche (600 - 800 CE).

Because of its particular shape and size. This cup was possibly used

within the context of the ceremony of ritual blood consumption.

-

Ceramic with sculpted representation of a dog, also identified in the

iconographic scene represented on the cup. Moche (400 - 600 CE).

|

|

Ceremonial sacrifice

-

Ceramic depicting a sacrifice at a mountain peak. Moche (600 - 800

CE). This representation suggests sacrifices either took place at

mountaintop or were symbolically related to the river sources.

- Tumi, or ceremonial knife. Moche (600 - 800 CE).

- Ceremonial comb depicting a sacrifice. Moche (600 - 800 CE).

-

Depiction of fight between Aia Paec and crab deity. Moche (600 - 800

CE).

-

Bone fragment (Femur) showing evidence of the wound inflicted on a

prisoner during the sacrifice ceremony. This fragment was found

embeded in the foot of an official sculpted upon Huaca Cao Viejo's

main facade. The finding establishes a direct correlation between

sacrifice as a ceremonial event described in art and the real

manifestation of the individual participating in the event.

|

|

Sacrificial rope

-

Ceramic depicting a figure with a rope around the neck, kneeling on a

spherical platform. Moche (600 - 800 CE).

-

Jar with sacrificial rope tied around the neck. Moche (200 - 400 CE).

The jar can be interpreted as a metaphor for the prisoner’s body both

are containers of blood and sacred liquids.

-

Sacrificial rope made from junco reed. Moche (200 - 400 CE). This type

of rope is found in the tombs of sacrificed individuals.

|

|

Weapons

-

Wooden clubs originally covered with a metal finish and probably

broken during combat. Moche (200 - 400 CE). Clubs were used not only

as weapons, but also as a symbol of power among religious leaders.

-

Ceramic depicting weapons bundle. Moche (600 - 800 CE). The weapons

bundle motif was frequently singled out and synthesized by the Moche,

which suggests that the appropriation of the warrior’s attire could

have been a symbol of victory in battle.

|

|

Warriors

-

Moche warrior with conic helmet, sitting on stepped platform. Moche

(200 - 800 CE).

-

Moche officiant or warrior with turban and moustache. Moche (200 - 800

CE).

- Warrior with headdress and club. Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE).

-

Lambayeque officiant or warrior. Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE). Later

societies, such as the Lambayeque, inherited ideological concepts from

the Moche and expressed common political and religious values in their

own times.

|

Rituals of death room

In this room the expressions associated with the funeral practices of the

Moche are presented. The funerary context of the two main tombs of the Huaca

Cao Viejo is exhibited and the relationship between funerary techniques and

Moche concepts on the “Beyond” is emphasized. Because the ritual experience is

displayed through performative acts, impossible to register through

archaeological work, the museography emphasizes the dynamic character of the

funeral ceremonies incorporating musical sounds that are reconstructed through

the archaeo-musicological analysis. In this room also refers to the

production, consumption and exchange of sacred liquids through the exhibition

of an important funerary set of ceramics in the form of containers, showing

that the currents and flows were part of a mythical circulation system, in

which metaphorically participated the blood of the sacrificed, the water of

the rivers and the chicha de jora. It is shown that to this day the

ritual control of fluids and flows is in charge of women.

|

Rituals of Death

Within the heart of the pyramids, the tombs didn’t constitute stagnant

or final places, but rather sacred passageways through which the dead

passed on their way to the world of the Ancestors.

-

In the Moche symbolic system, the natural process of death was

conceived of as a condition for rebirth and regeneration.

-

Death was represented as a messenger of life and fertility, and even

after the conclusion of the burial ceremonies, the living sought to

penetrate the spheres of the dead. The evidence at Huaca Cao Viejo

suggests that during certain funerary rituals, the Moche damaged the

pyramidal structures and reopened tombs to interact with their

ancestors.

-

Through song and offerings, the living beings revitalized and

reinvigorated death, which endowed the earth and the world of the

living with life and fertility.

|

|

Bone flutes

Lambayeque (900 - 1200 CE).

-

In the first stage of the metaphysical journey of the dead, men and

women of high rank were raised up with the aid of funerary music and

its transformative power.

-

The bone instruments, beyond producing very particular musical scales,

symbolized the process of transfiguration of the materiality of death

into a source of sound and rhythm.

|

|

Reused Tomb

In 1998, archaeologists of the El Brujo Archaeological Program made a

discovery that uncovered a complex funerary technique, mysterious to us,

but probably common among the Moche.

-

The findings indicate that approximately one hundred years after

having buried an adult woman of high rank in Huaca Cao Viejo, the

Moche ceremonially reopened the tomb and removed the main body from

its original resting place.

-

In its stead, they buried an approximately sixty-year-old woman. The

offerings, correspanding to the Middle Moche period, were reused and

intermingled with the new ones. The tomb was altered and readjusted to

the symbolic needs of the newly deceased.

|

|

Companion's Tomb

Very close to the Lady of Cao's tomb, the grave pits of three companions

were found. One of the burials corresponded to an approximately 20- or

30-year-old male.

The principle elements found with the individual, offerings

corresponding to the Early Moche period, allow him to be identified as a

priest associated with the rituals of water and the rainbow. He was

probably an important member of the court of the Moche ruler.

-

Ceremonial attire made from leather, with details and ornaments in

golden copper and shell incrustations. Some parts of the garment were

covered in feathers.

-

Ceramic depicting a figure holding lime container and chewing coca

leaves.

- Crest of feathers from marsh foul or cranes.

- Ceramic depicting ray fish.

-

Gallinazo-style ceramic depicting dignitary praying within a

ceremonial chamber.

|

See also

Sources

Location