The National Museum of Anthropology (Spanish: Museo Nacional de Antropología,

MNA) is a national museum of Mexico. It is the largest and most visited museum

in Mexico. Located in the area between Paseo de la Reforma and Mahatma Gandhi

Street within Chapultepec Park in Mexico City, the museum contains significant

archaeological and anthropological artifacts from Mexico's pre-Columbian

heritage, such as the Stone of the Sun (or the Aztec calendar stone) and the

Aztec Xochipilli statue.

Designed in 1964 by Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Jorge Campuzano, and Rafael Mijares

Alcérreca, the monumental building contains exhibition halls surrounding a

courtyard with a huge pond and a vast square concrete umbrella supported by a

single slender pillar (known as "el paraguas", Spanish for "the umbrella").

The halls are ringed by gardens, many of which contain outdoor exhibits. The

museum has 23 rooms for exhibits and covers an area of 79,700 square meters

(almost 8 hectares) or 857,890 square feet (almost 20 acres).

|

Entrance to the National Museum of Anthropology.

The National Museum of Anthropology (Spanish: Museo Nacional de

Antropología, MNA) is a national museum of Mexico. It is the largest and

most visited museum in Mexico.

-

Located in the area between Paseo de la Reforma and Mahatma Gandhi

Street within Chapultepec Park in Mexico City, the museum contains

significant archaeological and anthropological artifacts from Mexico's

pre-Columbian heritage, such as the Stone of the Sun (or the Aztec

calendar stone) and the Aztec Xochipilli statue.

|

|

Museum courtyard.

Designed in 1964 by Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Jorge Campuzano, and Rafael

Mijares Alcérreca, the monumental building contains exhibition halls

surrounding a courtyard with a huge pond and a vast square concrete

umbrella supported by a single slender pillar (known as "el paraguas", Spanish for "the umbrella").

-

The halls are ringed by gardens, many of which contain outdoor

exhibits.

-

The museum has 23 rooms for exhibits and covers an area of 79,700

square meters (almost 8 hectares) or 857,890 square feet (almost 20

acres).

|

|

Clay acrobat.

Ceramic art recovered from Tlatilco, commonly known as the "Acrobat".

c. 1300 - 800 BCE.

-

Some scholars think that this figure represents a shaman in

transformation pose.

-

Tlatilco is noted in particular for its high quality pottery pieces,

many featuring Olmec iconography, and its figurines, including

Olmec-style baby-face figurines.

-

See more at

Tlatilco - Wikipedia.

|

|

Teotihuacan mask.

Three-dimensional stone masks depicting a conventionalized human-like

face are abundant in the sculptural style associated with the great

Central Mexican city of Teotihuacan.

-

With its geometrically rendered horizontal brow, triangular nose, and

oval mouth and eyes, this mask depicts an idealized facial type that

seems to function as a symbol, rather than a portrait, similar to

other standardized motifs present in the art of Teotihuacan.

-

They may represent a local version of the Mesoamerican maize deity,

the stony faces as metaphors for maize seeds to be planted and reborn

as tender sprouts.

|

|

Terracotta pottery from Tlapacoya.

This terracotta pottery perfectly illustrates the type of plastic

composition loved by the Olmecs.

-

The jaguar's eyes are represented in the form of an elongated

rectangle, surmounted by the famous flame motif.

-

The mouth appears in the form of an inverted U-shaped motif,

ornamented with a cross that specialists call the “Olmec cross”.

- Between the eyes, the V-motif is clearly visible.

-

Finally, the small concentric circles are arranged on both sides of

the feline.

|

|

Terracotta pottery from Tlapacoya.

The same profile composition appears all around the ceramic, reproducing

the same elements.

|

|

Baby-face figurine.

The "baby-face" figurine is a unique marker of Olmec culture,

consistently found in sites that show Olmec influence.

-

These ceramic figurines are easily recognized by the chubby body, the

baby-like jowly face, downturned mouth, and the puffy slit-like eyes.

-

The head is slightly pear-shaped, likely due to artificial cranial

deformation.

- Baby-face figurines are usually naked, but without genitalia.

-

Their bodies are rarely rendered with the detail shown on their faces.

-

See more at

Olmec figurine - Wikipedia.

|

|

Baby-face figurine.

Also called "hollow babies", these figurines are generally from 25–35 cm

(9.8–13.8 in) high and feature a highly burnished white- or cream-slip.

-

Given the sheer numbers of baby-face figurines unearthed, they

undoubtedly fulfilled some special role in the Olmec culture. What

they represented, however, is not known.

-

Michael Coe, says "One of the great enigmas in Olmec iconography is

the nature and meaning of the large, hollow, whiteware babies".

|

|

Olmec figurines.

Olmec figurines are archetypical figurines produced by the Formative

Period inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While not all of these figurines were

produced in the Olmec heartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of

Olmec culture.

-

These figurines are usually found in household refuse, ancient

construction fill, and, outside the Olmec heartland, graves.

-

The vast majority of figurines are simple in design, often nude or

with a minimum of clothing, and made of local terracotta.

-

See more at

Olmec figurine - Wikipedia.

|

|

Character of Atlihuayan.

The sculpture called Character of Atlihuayan, which possibly represents

an Olmec shaman, has on its back a kind of animal skin that appears to

be of a feline and contains engraved crosses framed in U-shapes with an

interior division at the bottom.

-

These crosses, some authors say, represent a “cultivation land near or

next to a stream of water”.

-

The Latin cross, which combines the vertical with the horizontal, in

the pre-Hispanic context is interpreted as the representation of the

feline's spots and its meaning is "the union of the directions of the

universe" and the "navel or center of the earth", or expresses simply:

the "directions of the earth".

|

|

The Monster of the Earth.

In the Central Plaza of Chalcatzingo, on a structure, this bas-relief

was located that shows the frontal view of the "monster of the earth".

-

The hollow, open, cruciform mouth is associated with caves, and plant

elements emanate from its four corners.

- The eyes are ovoid in shape and are framed by flaming eyebrows.

-

On the nose there is an oval-shaped cartouche framed by a motif with

incised ovals.

-

It is possible that it was used, in ritual acts, as a passageway to

the sacred area.

-

The original of this monument is currently in the Utica Museum of Art,

New York.

|

|

Blandine Gautier introduces us to "The King".

|

|

The King.

Reproduction of Monument 1 of Chalcatzingo called "El Rey" (The

King).

-

"El Rey" (The King) is a life-size carving of a human-like

figure seated inside a cave with a wide opening; the shape of the

opening represents one-half of a quatrefoil.

-

The point of view is from the side, and the entire cave appears

cross-sectional, with the cave entrance is seen to the right of the

figure.

-

The cave entrance is as tall as the figure, and scroll volutes

(perhaps indicating speech or perhaps wind) are issuing from it.

-

The cave in which the figure sits is equipped with an eye, and its

general shape could suggest that of a mouth.

-

Above the cave are a number of stylized objects which have been

interpreted as rain clouds, with exclamation-like objects ("!")

appearing to fall from them. These have been generally interpreted as

raindrops.

|

|

Reproduction of Monument 31 of Chalcatzingo.

Reproduction of Monument 31 of Chalcatzingo, showing a beaked feline

zoomorph atop a recumbent human. Note the 3 stylized raindrops

apparently falling from a "Lazy S" figure.

-

Monument 31 depicts a recumbent feline atop a human, perhaps attacking

him.

-

Three raindrops, like those in El Rey (The King), can be seen

falling from above.

|

|

Reproduction of Monument 31 of Chalcatzingo.

Interpretations of this scene range from the idea that raindrops falling

on the jaguar comprise a fertility metaphor to themes of bloodletting

and sacrifice.

|

|

Model of Teotihuacan.

Teotihuacan is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of

the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, 40

kilometers (25 mi) northeast of modern-day Mexico City.

-

Teotihuacan is known today as the site of many of the most

architecturally significant Mesoamerican pyramids built in the

pre-Columbian Americas, namely Pyramid of the Sun and Pyramid of the

Moon.

-

See more at

Teotihuacan - Wikipedia.

|

|

Restored portion of Teotihuacan architecture.

Restored portion of Teotihuacan architecture showing the typical

Mesoamerican use of red paint complemented on gold and jade decoration

upon marble and granite.

-

Architectural styles prominent at Teotihuacan are found widely

dispersed at a number of distant Mesoamerican sites, which some

researchers have interpreted as evidence for Teotihuacan's

far-reaching interactions and political or militaristic dominance.

-

A style particularly associated with Teotihuacan is known as

talud-tablero, in which an inwards-sloping external side of a

structure (talud) is surmounted by a rectangular panel

(tablero).

|

|

Reproduction of the feathered serpent in Teotihuacan.

Supernatural feathered serpents feature prominently in the art of

Teotihuacan and were associated with cosmological narratives, rulership,

and militarism.

-

Architects recreated the sacred landscape of a pyramid as a primordial

mountain with feathered serpents emerging from its rocky facades.

|

|

Reproduction of the feathered serpent in Teotihuacan.

Builders at the city of Teotihuacan created balustrades in form of

descending serpents so that those entering a grand staircase would be

greeted by the roaring heads of monumental, supernatural reptiles.

-

The serpent’s head displays conventionalized features consistent with

many of the zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms in Teotihuacan

sculpture and mural painting.

-

The deep-set eyes are surrounded by feathers, and the nostrils also

flare with feathered texture.

-

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid, one of the three largest buildings at

Teotihuacan, has balustrades that feature such serpent heads emerging

from floral motifs, their bodies undulating on the adjacent tiers of

the façade.

-

See more at

Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacan - Wikipedia.

|

|

Mural from the Tepantitla compound.

Apart from the pyramids, Teotihuacan is also anthropologically

significant for its complex, multi-family residential compounds, the

Avenue of the Dead, and its vibrant, well-preserved murals.

-

The creation of murals, perhaps tens of thousands of murals, reached

its height between 450 and 650.

-

The artistry of the painters was unrivaled in Mesoamerica and has been

compared with that of painters in Renaissance Florence, Italy.

|

|

Mural from the Tepantitla compound.

The more elite compounds were often decorated with elaborate murals.

Thematic elements of these murals included processions of lavishly

dressed priests, jaguar figures, the storm god deity, and an anonymous

goddess whose hands offer gifts of maize, precious stones, and water.

-

The Tepantitla compound provided housing for what appears to have been

high status citizens and its walls (as well as much of Teotihuacan)

are adorned with brightly painted frescoes.

|

|

Great Goddess of Teotihuacan.

Reproduction of a mural from the Tepantitla compound showing what has

been identified as an aspect of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan.

-

The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan (or Teotihuacan Spider Woman) is a

proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization (ca.

100 BCE - 700 CE), in what is now Mexico.

-

Defining characteristics of the Great Goddess are a bird headress and

a nose pendant with descending fangs.

-

In the Tepantitla mural, the Great Goddess wears a frame headdress

that includes the face of a green bird, generally identified as an owl

or quetzal, and a rectangular nosepiece adorned with three circles

below which hang three or five fangs. The outer fangs curl away from

the center, while the middle fang points down.

-

She is also always seen with jewelry such as beaded necklaces and

earrings which were commonly worn by Teotihuacan women.

-

Her face is always shown frontally, either masked or partially

covered, and her hands in murals are always depicted stretched out

giving water, seeds, and jade treasures.

-

Other defining characteristics include the colors red and yellow; note

that the Goddess appears with a yellowish cast.

-

In the depiction from the Tepantitla compound, the Great Goddess

appears with vegetation growing out of her head, perhaps

hallucinogenic morning glory vines or the world tree. Spiders and

butterflies appear on the vegetation and water drips from its branches

and flows from the hands of the Great Goddess.

-

Water also flows from her lower body. These many representations of

water led Caso to declare this to be a representation of the rain god,

Tlaloc.

-

See more at

Great Goddess of Teotihuacan - Wikipedia.

|

|

Great Goddess of Teotihuacan.

Below this depiction, separated from it by two interwoven serpents and a

talud-tablero, is a scene showing dozens of small human figures, usually

wearing only a loincloth and often showing a speech scroll.

-

Several of these figures are swimming in the criss-crossed rivers

flowing from a mountain at the bottom of the scene.

-

Caso interpreted this scene as the afterlife realm of Tlaloc, although

this interpretation has also been challenged, most recently by María

Teresa Uriarte, who provides a more commonplace interpretation: that

"this mural represents Teotihuacan as the prototypical civilized city

associated with the beginning of time and the calendar".

|

|

Netted Jaguar (left panel).

Shows a jaguar with the body of blue water, netting gives his body

substance.

-

The jaguar proceeds towards a temple walking on water filled with

all-seeing eyes of the Great Goddess.

|

|

Netted Jaguar (right panel).

|

|

Chalchiuhtlicue.

Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue (or other water goddess) from the Pyramid of

the Moon.

-

Chalchiuhtlicue ("She of the Jade Skirt") is an Aztec deity of water,

rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism.

-

Chalchihuitlicue wears a distinctive headdress, which consists of

several broad, likely cotton bands trimmed with amaranth seeds.

- Large round tassels fall from either side of the headdress.

-

Chalchihuitlicue typically wears a shawl adorned with tassels and a

skirt.

-

See more at

Chalchiuhtlicue - Wikipedia.

|

|

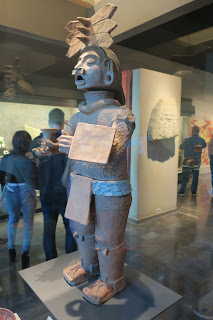

Xipe Totec.

Sculpture representing the god Xipetotec. He is upright, with his right

arm flexed with a claw glass in his hand, his left arm flexed, and his

hand in a position to hold some object. He is dressed in a pleated paper

headdress, flayed skin, necklace, maxtlatl, and sandals.

-

In Aztec mythology and religion, Xipe Totec or Xipetotec ("Our Lord

the Flayed One") was a life-death-rebirth deity, god of agriculture,

vegetation, the east, spring, goldsmiths, silversmiths, liberation,

and the seasons.

- Xipe Totec connected agricultural renewal with warfare.

-

He flayed himself to give food to humanity, symbolic of the way maize

seeds lose their outer layer before germination and of snakes shedding

their skin.

-

He is often depicted as being red beneath the flayed skin he wears,

likely referencing his own flayed nature.

-

Xipe Totec was believed by the Aztecs to be the god that invented war.

-

His insignia included the pointed cap and rattle staff, which was the

war attire for the Mexica emperor.

|

|

Xipe Totec.

Xipe Totec is represented wearing flayed human skin, usually with the

flayed skin of the hands falling loose from the wrists.

-

His hands are bent in a position that appears to possibly hold a

ceremonial object.

-

His body is often painted yellow on one side and tan on the other.

-

His mouth, lips, neck, hands and legs are sometimes painted red.

-

See more at

Xipe Totec - Wikipedia.

|

|

Reproduction of Stela 31 from Tikal.

Stela 31 was dedicated in 445 AD as the accession monument of Siyaj Chan

K'awiil II, also bearing two portraits of his father, Yax Nuun Ayiin, as

a youth dressed as a Teotihuacan warrior with a spearthrower in one hand

and a shield with the face of Tlaloc, the Teotihuacan war god.

-

This is a reproduction of the Tikal Stela 31 which reveals connection

that the Maya had with Teotihuacan during the Early Classic Period (AD

250 - 650).

-

The long inscription on the back of Stela 31 is the single most

important historical text from Tikal.

|

|

Reproduction of the feline man mural from Cacaxtla.

The northern wall shows a man dressed in a jaguar outfit and helmet,

standing on a jaguar-skinned serpent. .

-

This character has a bundle of darts dripping water from one end.

-

The feline man is associated with the rains that fertilize the earth.

|

|

Reproduction of the bird man mural from Cacaxtla.

The southern wall clearly presents a Maya dressed in a bird outfit and

helmet, riding on a plumed serpent.

-

The bird man is associated with Quetzalcoatl, the generous deity who

taught people the arts and agriculture.

|

|

Northern building's jamb.

On a blue background, a characters appear: a jaguar-man who pours water

into a Tlaloc pot.

|

|

Southern building's jamb.

On a blue background, a Maya with a snail, from which emerges a little

red-haired man—probably representing the sun.

|

|

The Creator of Xochicalco.

This bearded and fanged figure, standing on one knee and dressed in an

elaborate headdress, is called the “Creator”. This creature is

associated with the fertility and divine lineage of the ruling dynasties

of Xochicalco, as it has two members. These natural wonders of mutation

with images of cocoa leaves rise up the arms of the deity, run down his

back, tying themselves in a knot on his chest and descending, one to the

thigh and the other to the left forearm.

-

Xochicalco is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Miacatlán

Municipality in the western part of the Mexican state of Morelos.

-

See more at

Xochicalco - Wikipedia.

|

|

Chacmool from Mixco, Tlaxcala.

A chacmool (also spelled chac-mool) is a form of pre-Columbian

Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing

90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and

supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach.

-

These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to

the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial

offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys,

feathers and incense.

-

In an Aztec example, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli (a stone

bowl to receive sacrificed human hearts).

-

Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones.

-

Aztec chacmools bore water imagery and were associated with Tlaloc,

the rain god.

-

Their symbolism placed them on the frontier between the physical and

supernatural realms, as intermediaries with the gods.

|

|

Atlantean figure.

Column representing a great warrior, richly dressed, from Tula, Hidalgo.

-

He is standing with his arms close to his body, holding a dart-thrower

in his right hand and a knife and four arrows in his left, legs

together.

-

He wears a headdress of bands and feathers. Wearing earmuffs, a

stylized butterfly breastplate, bracelets and anklets. Dress with

maxtlatl knotted in front and sandals.

-

The piece is made up of four sections that are assembled using the

tenon and box system.

-

See more at

Atlantean figures - Wikipedia.

|

|

The Goddess of Fertility.

An upright female anthropomorphic sculpture, with her arms crossed over

her chest.

-

Dressed in a quechquémitl with a point at the front, a 3-wire

bracelet, discoidal earmuffs, a band headdress with circles inside and

the symbol of time crowning it.

- From Tula area, Hidalgo.

|

|

Standard bearer.

Erect male anthropomorphic standard-bearer, in an embracing attitude,

general shape: rectangular cubic body and rounded head, legs together

slightly apart, arms flexed in front, with disproportionate hands and

interlaced hands, leaving behind a vertical cylindrical perforation,

ovoid eyes inside sockets circular, mouth open. Dressed in a helmet with

4 smooth horizontal bands. Rectangular earmuffs, cheek protectors,

maxtlatl, sandals and anklets with bows.

- From the West End of Coatepantli, Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico.

|

|

Stone ballcourt goal.

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played

since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient

Mesoamerica.

-

Some ballcourts had upper goals, scoring on which would end the match

instantly.

- The stone ballcourt goals are a late addition to the game.

-

See more at

Mesoamerican ballgame - Wikipedia.

|

|

Character with animal helmet.

Anthropomorphic hollow figurine, in which a character is represented

wearing a helmet in the shape of a feathered coyote. From Tula, Hidalgo.

-

The piece is made on a ceramic mold of the plumbate type, covered with

shell mosaics that represent feathers and eyes.

-

The individual's face has fringed hair, a beard and mustache, made of

brown pearly shell, and both his upper teeth and those of the coyote

are made of bone.

- It bears a fragmented conical horn at the tip of its snout.

|

|

Mesoamerican ballgame.

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played

since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient

Mesoamerica.

-

The rules of the Mesoamerican ballgame are not known, but judging from

its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball,

where the aim is to keep the ball in play.

-

The Mesoamerican ballgame had important ritual aspects, and major

formal ballgames were held as ritual events. Late in the history of

the game, some cultures occasionally seem to have combined

competitions with religious human sacrifice.

-

See more at

Mesoamerican ballgame - Wikipedia.

|

|

Mesoamerican rubber ball.

The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs),

and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

-

Ancient Mesoamericans were the first people to invent rubber balls,

sometime before 1600 BCE, and used them in a variety of roles.

-

The Mesoamerican ballgame, for example, employed various sizes of

solid rubber balls and balls were burned as offerings in temples,

buried in votive deposits, and laid in sacred bogs and cenotes.

-

See more at

Mesoamerican rubber balls - Wikipedia.

|

|

Jaguar Cuauhxicalli.

Ocelotl (jaguar) cuauhxicalli, in which a crouching feline is

represented, with its jaws ajar. He has a container on his back, at the

bottom of which are two characters: huitzilopochtli and

tezcatlipoca making a self-sacrifice, piercing their ears with

awls. In turn, the walls present a band of chalchihuites, a

stream of water and feathers.

-

A cuauhxicalli (meaning "eagle gourd bowl") was an altar-like

stone vessel used by the Aztec to hold human hearts extracted in

sacrificial ceremonies.

-

In Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli is the deity of war, sun, human

sacrifice, and the patron of the city of Tenochtitlan.

-

Tezcatlipoca was a central deity in Aztec religion, and his main

festival was the Toxcatl ceremony celebrated in the month of May. The

God of providence, he is associated with a wide range of concepts,

including the night sky, the night winds, hurricanes, the north, the

earth, obsidian, hostility, discord, rulership, divination,

temptation, jaguars, sorcery, beauty, war, and conflict. His name in

the Nahuatl language is often translated as "Smoking Mirror" and

alludes to his connection to obsidian, the material from which mirrors

were made in Mesoamerica and which were used for shamanic rituals and

prophecy.

|

|

Temple of the Holy War (front).

The Teocalli (Temple) of the Sacred War is a Mexica monolith, named

after Alfonso Caso, and which he believes may be a scale representation

of a temple or the icpalli (royal chair) of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin

himself.

-

It was found in the vicinity of the National Palace, from where it was

removed in 1926.

|

|

Temple of the Holy War (back).

The carved reliefs celebrate the triumph of the Sun and the military

power of the Mexicas after the founding of their city, symbolically

represented in the scene on the rear façade in which a golden eagle

perches on a cactus. The patron god of the Mexica, Huitzilopochtli, and

the tlatoani Motecuhzoma II, escort the image of the Fifth Sun and all

the characters and symbols represented emit the war cry expressed by the

elements of water and fire that come out of their mouths.

-

Its symbolisms are an exaltation of the ideology of Mexica power, and

the religious principle of the sacred war, including the

representation of the eagle on a cactus, devouring human hearts.

-

It is commonly believed that it is a snake that devours, like the

National Shield of Mexico.

-

The first study of the monolith was carried out by Alfonso Caso, who

concluded that its symbolisms allude to the exaltation of war and its

official cosmogony, which affirmed a vital need for human sacrifices

and of blood to the gods.

|

|

Stone of Tizoc.

Temalácatl (Stone) de Tizoc, is a sculptural representation carved in

igneous rock (basalt porphyry) in a cylindrical shape, in whose upper

part it has a solar disk with a hole in the center, on the edge it has

carved its victories.

-

The images of the Sun were carved and the conquests of 15 towns that

were carried out during the government of Tizoc.

-

See more at

Stone of Tizoc - Wikipedia.

|

|

Stone of Tizoc (close-up).

The Stone of Tizoc, Tizoc Stone or Sacrificial Stone is a large, round,

carved Aztec stone. Because of a shallow, round depression carved in the

center of the top surface, it may have been a cuauhxicalli or

possibly a temalacatl.

-

The tlatoani (ruler) is dressed as a warrior with attributes of

huitzilopochtli and tezcatlipoca, subduing the caciques

of the conquered provinces.

- He has a radial groove made in the colony.

|

|

Chac mool anthropomorphic sculpture.

Chac mool anthropomorphic sculpture, represented in the characteristic

position: a reclining individual resting his trunk on a platform, his

head turned to the left, his legs forming an arc between his hands,

carrying a container or cuauhxicalli on his belly. Decorated with

quincunces, feathers, and hearts, his clothing consists of a

maxtlatl and sandals decorated with flint knives. He wears a

feathered headdress and bands decorated with a flower, bracelets,

anklets, necklaces, a pectoral, and earmuffs.

- From the Late Postclassic Period.

|

|

Model of the temple district of Tenochtitlan.

The city was divided into four zones, or camps; each camp was divided

into 20 districts; and each calpulli, or 'big house', was crossed

by streets or tlaxilcalli. There were three main streets that

crossed the city, each leading to one of the three causeways to the

mainland of Tepeyac, Iztapalapa, and Tlacopan.

-

Tenochtitlan's main temple complex, the Templo Mayor, was dismantled

and the central district of the Spanish colonial city was constructed

on top of it.

-

The great temple was destroyed by the Spanish during the construction

of a cathedral.

-

See more at

Tenochtitlan - Wikipedia.

|

|

Dead Warrior's Brazier.

Brazier decorated with the representation of a warrior. Dressed in a

mask in the shape of a skull, nose ring, earmuffs in the shape of human

hands and a headdress with bands with crescent moons. With traces of

yellow, red, blue, brown and black paint.

- From the Late Postclassic Period.

|

|

The Tlatelolco market.

The great market of Tlatelolco was the largest and most important

commercial center of the Aztecs. It was located southwest of the Templo

Mayor de Tenochtitlán and brought together thousands of pochtecas or

merchants daily who exchanged their products through direct barter.

-

To sell valuable objects, they accepted gold powder, copper axes, and

cocoa, which functioned as "merchandise coins."

-

Products arrived in Tlatelolco from as far away as Honduras and the

Caribbean Islands. Those in charge of their transport were the

tamemes or chargers.

-

When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they were amazed by the multitude of

people and the infinity of merchandise that was exhibited in a very

orderly manner.

|

|

The inside of a reconstructed Aztec house.

The ‘average’ Aztec house was plain and simple, whether you lived in a

town or the countryside. One story high, one main room, a rectangular

hut with an open doorway (onto a patio), the house backed onto the

street.

-

No chimney, no windows, the floor was usually of earth (sometimes

stone), and the walls either ‘adobe’ (dried mud bricks), ‘wattle and

daub’ (wooden strips woven together, covered in cheapo plaster) or (if

you were better off) stone - or a mix: adobe bricks on stone

foundations. In towns the outside walls were often whitewashed.

-

The roof was thatched and sometimes ‘gabled’ or (in towns) low and

flat.

-

The main room was just for sleeping and eating: no-one spent much time

there during the day.

-

Lighting was by small flaming torches (made of pine resin) - and from

the fire, in the centre of the house.

-

Sometimes - if you weren’t too poor - the kitchen was separate, in the

courtyard, which you shared with neighbours.

-

Close by the house would be the sweat bath (like a sauna), shaped like

an igloo (but hot). Then you might have small turkey houses, maybe

even bee hives.

-

Furniture: reed mat bed, wooden chest, broom, digging stick, tools,

seed basket, loom, hunting/fishing gear, water jar, pots, grinding

stone, griddle, and a little altar.

|

|

Statue of Coatlicue.

Coatlicue is represented as a woman wearing a skirt of writhing snakes

and a necklace made of human hearts, hands, and skulls. Her feet and

hands are adorned with claws and her breasts are depicted as hanging

flaccid from pregnancy. Her face is formed by two facing serpents (after

her head was cut off and the blood spurt forth from her neck in the form

of two gigantic serpents), referring to the myth that she was sacrificed

during the beginning of the present creation.

-

Coatlicue, wife of Mixcōhuātl, also known as Tēteoh īnnān ("mother of

the gods") is the Aztec goddess who gave birth to the moon, stars, and

Huītzilōpōchtli, the god of the sun and war.

-

The goddesses Toci "our grandmother" and Cihuacōātl "snake woman", the

patron of women who die in childbirth, were also seen as aspects of

Cōātlīcue.

-

See more at

Cōātlīcue - Wikipedia.

|

|

Blandine Gautier explains how the Mayan calendar works.

The Maya calendar is a system of calendars used in pre-Columbian

Mesoamerica and in many modern communities in the Guatemalan highlands,

Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.

-

The Maya calendar consists of several cycles or counts of different

lengths.

-

The 260-day count is known to scholars as the Tzolkin, or Tzolkʼin.

-

The Tzolkin was combined with a 365-day vague solar year known as the

Haabʼ to form a synchronized cycle lasting for 52 Haabʼ, called the

Calendar Round.

-

A different calendar was used to track longer periods of time and for

the inscription of calendar dates (i.e., identifying when one event

occurred in relation to others). This is the Long Count. It is a count

of days since a mythological starting-point.

-

See more at

Maya calendar - Wikipedia.

|

|

Aztec sun stone.

The sculpted motifs that cover the surface of the stone refer to central

components of the Mexica cosmogony. The state-sponsored monument linked

aspects of Aztec ideology such as the importance of violence and

warfare, the cosmic cycles, and the nature of the relationship between

gods and man.

-

In the center of the monolith is often believed to be the face of the

solar deity, Tonatiuh,[14] which appears inside the glyph for

"movement", the name of the current era.

-

The central figure is shown holding a human heart in each of his

clawed hands, and his tongue is represented by a stone sacrificial

knife (tecpatl).

-

The four squares that surround the central deity represent the four

previous suns or eras, which preceded the present era, "Four

Movement".

-

The first concentric zone or ring contains the signs corresponding to

the 20 days of the 18 months and five nemontemi of the Aztec solar

calendar.

-

The second concentric zone or ring contains several square sections,

with each section containing five points.

-

The third and outermost ring contains two fire serpents. Xiuhcoatl,

take up almost this entire zone.

-

See more at

Aztec sun stone - Wikipedia.

|

|

Head of Coyolxauhqui.

Monumental head sculpture of the goddess coyolxauhqui (lunar goddess),

shows closed eyes, gold bells on her cheeks, lunar mustache and

triangular bezote, circular earmuffs as solar symbols. In her hair she

wears feathers, and at the base of her she has symbols linked to war and

sacrifice.

-

As usual, she is shown decapitated and with closed eyelids, as she was

beheaded by her brother, Huitzilopochtli.

-

See more at

Coyolxāuhqui - Wikipedia.

|

|

Coatlicue of Cozcatlán.

Sculpture with the anthropomorphized representation of the goddess

Coatlicue. Represented standing with her arms bent and her hands in

front of her, she has a gaunt face. She is dressed in her signature

skirt of entwined snakes, but she is bare-chested of hers, plus she is

decked out in circular earmuffs. She has a chest piercing on her.

-

Coatlicue, wife of Mixcōhuātl, also known as Tēteoh īnnān ("mother of

the gods") is the Aztec goddess who gave birth to the moon, stars, and

Huītzilōpōchtli, the god of the sun and war.

-

The goddesses Toci "our grandmother" and Cihuacōātl "snake woman", the

patron of women who die in childbirth, were also seen as aspects of

Cōātlīcue.

-

See more at

Cōātlīcue - Wikipedia.

|

|

Mausoleum of the Centuries.

Reconstruction of a rectangular commemorative altar. On the walls it has

coverings made from tezontle plates carved with the representation of a

skull and crossed bones as a tzompantli.

- From the Late Postclassic Period.

|

|

The Central Courtyard Umbrella.

Courtyard with a huge pond and a vast square concrete umbrella supported

by a single slender pillar (known as "el paraguas", Spanish for "the

umbrella").

|

|

Entrance to the reproduction of the mausoleum of K'inich Janaab'

Pakal I.

Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I, also known as Pacal or Pacal the Great (March

603 – August 683), was ajaw of the Maya city-state of Palenque in

the Late Classic period of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican chronology.

- He acceded to the throne in July 615 and ruled until his death.

- Pakal reigned 68 years.

-

After his death, Pakal was deified as one of the patron gods of

Palenque.

|

|

Mounted funerary jewelry of Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I.

Anthropomorphic Pakal mask, made up of a mosaic of 349 green stone

fragments, with shell eyes and obsidian irises, with cranial

deformation. Open eyes, hooked nose, open mouth with a bead inside.

- From the Late Classic Period.

|

|

Head of Pakal II (front) and head of Pakal I (back).

Front: Possibly it represents Pakal II, although it could represent his

wife or his mother. Back: Pakal head in stucco.

- From Palenque, Chiapas, México.

|

|

Reproduction of the mausoleum of K'inich Janaab' Pakal I.

Pakal was buried in a colossal sarcophagus within the largest of

Palenque's stepped pyramid structures, the building called Bʼolon Yej

Teʼ Naah "House of the Nine Sharpened Spears" in Classic Maya and now

known as the Temple of the Inscriptions.

-

His skeletal remains were still lying in his sarcophagus, wearing a

jade mask and bead necklaces, surrounded by sculptures and stucco

reliefs depicting the ruler's transition to divinity and figures from

Maya mythology.

-

Traces of pigment show that these were once colorfully painted, common

of much Maya sculpture at the time.

|

|

Reproduction of the mausoleum of K'inich Janaab' Pakal I

(close-up).

|

|

Painting of Pakal in his tomb.

|

|

Photo of the Temple of the Inscriptions in Palenque.

The Temple of the Inscriptions is the largest Mesoamerican stepped

pyramid structure at the pre-Columbian Maya civilization site of

Palenque.

-

The structure was specifically built as the funerary monument for

K'inich Janaab' Pakal, ajaw or ruler of Palenque in the 7th century.

|

|

The Central Courtyard Umbrella (close-up).

|

See also

Sources

Location