The Zenu people of Colombia are an Indigenous group with deep historical roots in the Caribbean lowlands, particularly in the valleys of the Sinu and San Jorge rivers.

Flourishing from around 200 BCE to 1600 CE, they developed sophisticated systems of hydraulic engineering to manage seasonal flooding, transforming vast wetlands into fertile agricultural land.

Their society was organized into provinces—FinZenu, PanZenu, and Zenufana—each with distinct roles in governance, agriculture, and gold production. Women held prominent roles in Zenu society, often symbolizing fertility and wisdom, and were even known to lead religious centers, such as the female chief Toto who governed FinZenu during the Spanish conquest.

Gold held profound cultural and spiritual significance for the Zenu. They mastered the lost-wax casting technique to create intricate ornaments, often depicting animals like birds, fish, and jaguars. These pieces weren’t merely decorative—they symbolized fertility, power, and the interconnectedness of life. Gold breastplates, earrings, and pendants were worn during ceremonies and buried with the dead, reflecting beliefs in rebirth and the afterlife. The Spanish conquistadors were drawn to this wealth, and much of the Zenu’s gold was looted during colonial expeditions.

Today, the legacy of Zenu gold craftsmanship is preserved at the Museo del Oro Zenu in Cartagena. Located in the heart of the walled city near Plaza Bolívar, this museum showcases over 500 gold artifacts, along with ceramics, bone carvings, and shell pieces that reflect the Zenu worldview and artistry4. The exhibits explore themes like amphibious living, social organization, and the symbolic role of women. Visitors can admire the unique gold weave patterns and animal figurines, which echo the Zenu’s reverence for nature and their environment.

Though smaller than Bogotá’s Gold Museum, Cartagena’s Zenu Gold Museum offers an intimate and insightful look into one of Colombia’s most resilient Indigenous cultures. It’s free to visit and includes multimedia presentations that deepen the experience. The museum not only honors the Zenu’s artistic achievements but also serves as a reminder of their enduring presence—many Zenu descendants still live in Colombia today, continuing to fight for land rights and cultural recognition.

|

Facade of the Zenu Gold Museum

|

|

«SERVICES

All our services are free INFORMATION

Enjoy library and cultural program services in the Bartolomé Calvo library and the Banco de la Republica building.» |

|

«6,000 years amid land and water»

|

|

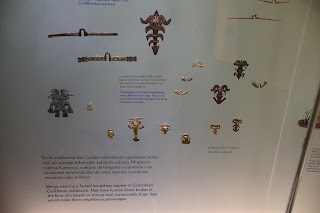

Breastplate with landscape with burial mounds and spectacled

caimans |

|

Staff finials in the form of crab pincer with spectacled caimans |

|

Feline pendant |

|

Rattle head in the form of an ibis |

|

Amid land and water «Over a period of thousands of years, vastly diverse amphibious worlds have developed in inland and coastal areas of Colombia's Caribbean region. In these ancient landscapes, wet rainy seasons follow hot dry seasons in a never-ending cycle. Boundaries between land and water move as floodwaters rise and fall. Green plains become marshes, and where before you used to walk, now you have to sail. The land is transformed, sometimes unpredictably. The inhabitants of these worlds prepare for life in times of flood and drought. The rhythm of life has taught them to change their food, their home, and their skin. In the past, amphibious societies depicted their peers in the air, on land and in water on musical instruments, staff finials and body ornaments. Birds, the lords of the skies, are protagonists on metal, pottery, stone and shell artifacts; mammals, reptiles and fish are less common.» |

|

Human-crustacean pendants

|

|

Beings with forked headdresses

|

|

Frogs and toads |

|

Boat-billed herons |

|

Herons |

|

Stork |

|

Staff finial |

|

Muscovy Duck |

|

Ibises or limpkins |

|

«Curassows, pigeons, owls, tinamous, parrots, scavenger birds and some birds of pray need well-preserved, mature forests, which have now disappeared. Herons, ibises, limpkins, spoonbills, cormorants and ducks closely follow water movements in order to determine their feeding, reproduction and house building strategies.» |

|

«Certain birds can be recognized in these objects by the shapes of their beaks, the size of which is frequently exaggerated. Craftsman adorned many of them with the curly crest of the curassow.» |

|

Pink spoonbills |

|

Coroncoros |

|

Felines |

|

«The different postures and attitudes of the felines in these objects illustrate the close harmony that existed between these predators.» |

|

Choose and move to eat «The animal species that were eaten by amphibious societies were selected on the basis of what they knew about the habits and life cycles of those species and how they viewed the world. Freshwater fish were preferred for eating, even at places near the sea. Marine and freshwater mollusks were gathered both on the coast an in the interior. Capybara, hicotea turtle, iguana, spectacled caiman, deer and paca, all inhabitants of marshes and forests, completed the diet. Despite their great abundance and diversity, birds were favored less in the kitchen. People learned to move to the same rhythm as those species. When water levels were low, they follow the fish that migrated upstream from the marshes to spawn. At the start of the rainy season, they moved toward the beaches to hunt for hicotea turtles and collect their eggs. At night, they hunted nocturnal mammals.» |

|

Building with nature «From the 9th century before the current era, and for around two thousand years, amphibious societies transformed the landscape so they could live on the floodable plains of the Mompox Depression. They built an extensive hydraulic system of canals and ridges to run off excess water and sediments during cyclical periods when the Cauca and San Jorge rivers burst their banks. In the rainy season, the ridges meant that they could continue their agricultural activities above the level of the water. And in the dry season, they used the sediments deposited in the canals during the flood to fertilize the ridges. Coca, corn, sweet potato, cassava, chill pepper, pumpkin and passion fruit were grown on a seasonal basis. The ridges were arranged in patterns, aesthetically and based on their use and an ideal order of the world. There were long ones, perpendicular to the straight courses of the natural channels; on the outside of meanders, they were fan-shaped and, on the inside, they were like fishbones, plaited and funnelled. Ridges near the artificial platforms on which they built their homes were domestic vegetable gardens and were like checkerboards. Building and maintaining the waterway system was part of everyday family life. Social links and links with their territory flowed with the movement of the waters.» |

|

Distribution of female figures in the region explored by this

museum |

|

Pottery figures of women |

|

N-shaped nose rings |

|

Metal breastplates |

|

Metal breastplate |

|

Earring for many people «Semi-circular, filigree earrings were made for almost two thousand years by various societies on the Caribbean plains, the San Jacinto Range, and in the lower-Magdalena region. They were probably worn by various social segments. Because of their different shapes, we can assume that they were worn by people of all ages. Over the course of this lengthy tradition of producing earrings, differences of style can be seen in terms of alloys, decorations, sizes, fills and forms that were developed in different regions and at different times. The production technique and shape remained invariable throughout. Unlike filigree work today, where soldered strands are used in Mompox and Ciénaga de Oro, pre-Hispanic filigree was done by casting using the lost wax method. Whereas contemporary goldsmiths create designs with metal strands, their forbears used strands of wax.» |

|

Goldwork group: Group of artifacts made in a particular geographic area and a specific period |

|

Earrings

|

|

Lost wax casting |

|

Hammering and embossing

|

|

The transformative power of blowing |

|

Sound universes «The sounds made by these wind instruments from the Lower Magdalena Region and the San Jacinto Range could have been ways of communicating, sound languages for establishing dialogues with various beings in the environment —animals, rivers, plants, mountains— on specific social occasions. These flutes and ocarinas were tuned, intentionally, to produce relationships between the tones, which are very different from those made by western instruments. They produce tones which differ from the tempered western system of twelve semitones that have a symmetrical distance between each one and which is adjusted mathematically. Flutes illustrate the numerous technical decisions that this traditions craftsmen made. Some relate to the shape: the resonating chamber consists of two cones and the distance between the tone holes is proportional to the size of the instrument: the length of the windway also depends on this Other decisions relate to the clay, the polishing —they were polished inside— and firing conditions. All of them are exceptional, unique characteristics of these wind instruments.» |

|

Flutes, ocarinas and shell trumpets «Players used these instruments to establish a dialogue with humans and animals. Although the sounds the ocarinas made did not coincide with those of the birds depicted in them, musicians could have guided the sound experience to evoke the birdsong.» |

|

Working with shells |

|

Shells of snails and bivalves

|

|

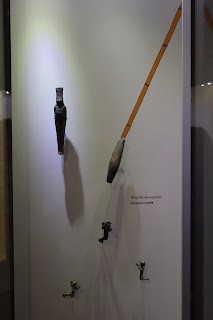

Enigmatic characters «This iconic figure was a symbol that was adopted and given diverse meanings by different societies separated in time and space, from the beginning of our era to the 17th century and from southwest Colombia to Mexico. These pendants repeat multiple variations of a masked person, as if he or she were taking part in a ritual. From a schematic body and flat legs rises a great feathered headdress, the face transformed with animal features and with instruments in the hands. What could it have meant for the inhabitants of the amphibious worlds over a period of seventeen centuries?» |

|

Enigmatic characters

|

|

Blowpipe nozzle |

See Also

-

Convent of La Popa

-

San Felipe de Barajas Castle

-

Cartagena

-

Church of Santo Domingo

-

Cathedral of Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Source

Location