Raquira is a vibrant little gem tucked away in the Boyaca department of

Colombia, about 3.5 hours from Bogota. Its name comes from the Chibcha

language and means “Village of the Pans”—a nod to its deep-rooted tradition in

pottery that dates back to pre-Hispanic times.

Often called the handicraft capital of Colombia, Raquira is famous for its

colorful facades, cobbled streets, and artisan workshops that line the town

like a living gallery. Nearly three-quarters of its economy revolves around

handmade crafts—especially ceramics, but also textiles, hammocks, and woven

goods. On Sundays, the town comes alive with a bustling market where artisans

sell their wares directly to visitors.

The town’s central plaza is a visual feast, dotted with whimsical ceramic

sculptures and surrounded by shops and cafés. Nearby, the Monastery of La

Candelaria, founded in the 17th century, offers a peaceful retreat steeped in

history. And if you’re hungry, don’t miss a hearty cazuela boyacense—a

local stew that’s as comforting as the town itself.

|

Raquira’s colorful houses

Raquira’s colorful houses are like

a joyful explosion of paint and personality—each one a canvas that

reflects the town’s artistic soul. Nestled in the heart of Boyaca, this

small Colombian town is famous for its vividly painted facades, where

homes and shops are adorned in bold hues of turquoise, ochre, crimson,

and lime green, often accented with hand-painted motifs, ceramic

decorations, and whimsical sculptures.

-

Walking through Raquira feels like stepping into a storybook. The

cobblestone streets are lined with buildings that seem to compete for

attention, each more vibrant than the last. Many of the houses double

as artisan workshops or storefronts, proudly displaying handmade

pottery, hammocks, and woven goods that spill out onto the sidewalks.

-

This explosion of color isn’t just for show—it’s a living expression

of the town’s identity as the “Cradle of Colombian Handicrafts.” The

tradition of decorating homes in such a lively way is rooted in both

indigenous Muisca heritage and colonial influences, blending centuries

of culture into a single, joyful aesthetic.

-

If you’re ever there on a sunny afternoon, the light bouncing off

those painted walls makes the whole town glow. It’s not just

picturesque—it’s a celebration of creativity in every brushstroke.

|

|

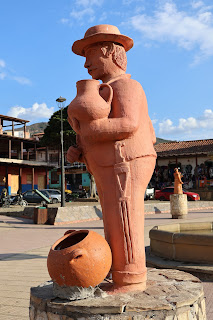

Raquira main park

Raquira’s Main Park is the beating heart

of this colorful artisan town—and it’s impossible to miss the whimsical

clay statues that give it such a distinctive charm. Right in front of

the Iglesia San Antonio de la Pared, the park is dotted with large

terracotta sculptures that pay tribute to the town’s deep-rooted ceramic

tradition and its people.

-

These statues aren’t just decorative—they’re storytelling pieces.

You’ll find figures of potters at work, peasant women in traditional

ruanas, musicians, and even a cheeky little fountain modeled after the

famous Manneken Pis, but with a local twist. Each sculpture is

handcrafted and painted in earthy tones, echoing the natural clay that

has shaped Raquira’s identity for centuries.

-

The park itself is a lively gathering spot, especially on weekends

when artisans set up stalls nearby and music fills the air. It’s a

place where tradition, creativity, and community come together in the

most delightful way.

|

|

Saint Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary

She is often

depicted holding a young Mary—sometimes resting on her arm or standing

beside her—symbolizing her role in nurturing and teaching the future

Mother of Christ. While a candle isn’t a universal attribute of Saint

Anne, in some artistic interpretations, it may appear as a symbol of

guidance, wisdom, or spiritual enlightenment, especially in depictions

emphasizing her role as a teacher.

|

|

Saint Mary, the mother of Jesus

This is a deeply symbolic

and visually rich depiction. While not one of the most standardized

Marian iconographies in Catholic tradition, this representation appears

to be a localized or devotional variation that blends traditional

elements with regional or artistic interpretation.

-

The staff can symbolize her role as a spiritual guide or

protector—echoing the shepherd’s staff, which is more commonly

associated with Christ or Saint Joseph. In Marian imagery, it may also

suggest her authority as Queen of Heaven or her journey during the

Flight into Egypt.

-

The dove is a powerful symbol of the Holy Spirit, peace, and divine

mission. When held by the Christ Child, it emphasizes his role as the

bringer of peace and the embodiment of the Spirit. This gesture also

evokes the moment of Jesus’ baptism, where the Holy Spirit descended

like a dove.

-

This composition may be unique to a particular church, region, or

artisan tradition—especially in places like Colombia, where religious

art often fuses canonical themes with local storytelling. It’s

possible the statue is meant to evoke a sense of maternal guidance and

divine peace, rather than referencing a specific biblical scene.

|

|

Saint Anthony of Padua

This is a classic and deeply symbolic

depiction of Saint Anthony of Padua, one of the most beloved saints in

Catholic tradition—especially among Franciscans.

-

The baby Jesus resting on a book on Saint Anthony’s left forearm

refers to a mystical vision he reportedly had, where Christ appeared

to him as a child. The book is typically the Bible, symbolizing

Anthony’s profound knowledge of Scripture and his role as a Doctor of

the Church.

-

The Franciscan cord around his waist, with its characteristic three

knots, represents the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—core

tenets of Franciscan life.

-

The monk’s rosary tied to his waist emphasizes his devotion to prayer

and the contemplative life.

-

This image is not just artistic—it’s theological. It captures Saint

Anthony’s identity as a preacher, scholar, and mystic, as well as his

intimate spiritual connection with Christ. The peaceful, tender way he

holds the child Jesus reflects his humility and love, which is why

this image is so cherished in churches and homes around the world.

|

|

Fray Francisco de Orejuela

The Franciscan friar credited

with founding Raquira is Fray Francisco de Orejuela. He established the

town on October 18, 1580, during the Spanish colonial period, as part of

the broader Franciscan mission to evangelize and organize indigenous

communities in the New Kingdom of Granada—modern-day Colombia.

-

Fray Francisco de Orejuela’s role was both spiritual and

administrative. As a missionary, he helped introduce Christianity to

the Muisca people of the region, while also laying the groundwork for

a structured colonial settlement. His efforts were part of a larger

Franciscan strategy to create “doctrinas”—settlements centered around

a church and school where friars could teach the faith and Spanish

customs.

-

Although detailed biographical records about Orejuela are scarce, his

legacy lives on in Raquira’s enduring Franciscan character. The town’s

church, Iglesia San Antonio de la Pared, and its proximity to the

Monastery of La Candelaria—the first monastery in the interior of

Colombia—are testaments to the deep roots the Franciscans planted

there.

|

|

Muisca potter with his kiln

The Muisca people—indigenous to

the highlands of what is now central Colombia—were master potters long

before the Spanish arrived, and their legacy lives on in Raquira, whose

name in the Chibcha language means “City of Pots.” This region was a hub

of ceramic production even in pre-Hispanic times, and the Muisca

developed remarkably refined techniques for working with clay.

-

Their pottery was both functional and ceremonial. They crafted cooking

vessels, storage jars, and ritual items, often decorated with

geometric patterns and symbolic motifs. The clay was sourced locally

from riverbeds and hills, then hand-kneaded and shaped using simple

tools or coiling methods. The Muisca didn’t use potter’s

wheels—instead, they relied on their hands and intuition, which gave

their pieces a distinctive organic quality.

-

As for their kilns, the Muisca used open-pit or rudimentary updraft

kilns, fueled by wood. These early ovens were carefully managed to

reach the high temperatures needed to harden the clay, though they

lacked the precision of modern kilns. The firing process was a

communal event, often tied to seasonal cycles and spiritual practices.

-

Today, Raquira’s artisans still draw from this ancient heritage. While

modern kilns and glazes have been introduced, many potters continue to

use traditional wood-fired ovens, preserving the earthy textures and

warm tones that have defined the region’s ceramics for centuries.

|

|

Muisca man

The Muisca were one of the four great

civilizations of the Americas before the Spanish conquest—alongside the

Aztec, Maya, and Inca. They inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, a

high plateau in the Eastern Andes of present-day Colombia, covering

areas around modern-day Bogota, Boyaca, and Cundinamarca.

-

The Muisca were skilled farmers, weavers, and goldsmiths, known for

their advanced agricultural techniques like terracing and irrigation.

They cultivated maize, potatoes, quinoa, and cotton, and traded salt,

emeralds, and textiles with neighboring peoples.

-

Their society was organized into a confederation of chiefdoms, led by

rulers known as the zipa (in the south) and the zaque (in the north).

A third spiritual leader, the iraca, governed the sacred city of

Suamox (now Sogamoso).

-

The Muisca had a rich spiritual life centered around nature worship.

They revered deities like Sué (the sun god), Chía (the moon goddess),

and Chibchacum, the protector of merchants and metalworkers. Sacred

lakes, caves, and rocks were sites of ritual offerings, often

involving gold figurines called tunjos.

-

They also gave rise to the legend of El Dorado—a ritual in which a new

ruler was covered in gold dust and dove into Lake Guatavita as an

offering to the gods.

-

Though the Spanish conquest in the 16th century disrupted their way of

life, the Muisca left a lasting imprint on Colombian identity. Their

language, Muysccubun, is being revived, and their traditions continue

to influence local crafts, especially in towns like Raquira.

|

|

Muisca potter shaping a vase with his hands

The Muisca

potters were true masters of hand-built ceramics, long before the

invention or adoption of the potter’s wheel in their region.

-

Their techniques were rooted in coiling and pinching, where long ropes

of clay were stacked and smoothed to form vessels like vases, bowls,

and ceremonial urns. This method gave their pottery a distinctive,

organic feel—each piece subtly unique, shaped by the artisan’s hands

and intuition.

-

They used locally sourced clay, often mixed with tempering materials

like sand or crushed stone to improve durability. Once shaped, the

vessels were dried and then fired in open-pit or rudimentary updraft

kilns, fueled by wood. These kilns required careful control of heat

and airflow, and the firing process was often a communal, even

spiritual, event.

-

Muisca pottery wasn’t just functional—it was symbolic. Many vases were

decorated with geometric patterns, spirals, and stylized animals,

often painted with natural pigments. These motifs held cosmological or

ritual significance, reflecting the Muisca’s deep connection to nature

and the divine.

-

Their legacy lives on in towns like Raquira, where modern artisans

still echo these ancient techniques, blending tradition with

contemporary creativity.

|

|

Clay donkey carrying ceramic pots

|

|

Muisca woman with spinning spindle in her right hand

The

women of the Muisca people were highly skilled artisans, especially

renowned for their weaving and textile production, which played a

central role in both their economy and cultural identity.

-

They primarily worked with cotton, which was cultivated in the warmer

lowlands and traded up to the highlands where the Muisca lived. Using

simple looms and hand-spinning techniques, Muisca women wove mantles,

bags, nets, and small cloths—some of which even served as a form of

currency. Their textiles featured geometric and interlocking designs,

such as spirals and stepped patterns, often imbued with symbolic

meaning.

-

In addition to cotton, they were also adept at basket-weaving and

featherwork, creating intricate items used in daily life, trade, and

ceremonial contexts. These crafts weren’t just utilitarian—they were

expressions of identity, status, and spirituality.

-

Weaving was considered a sacred and feminine art, passed down through

generations. The act of creating cloth was deeply tied to the Muisca

worldview, linking the threads of the loom to the threads of life and

the cosmos.

|

|

Muisca man with a jug in his left hand

|

|

Muisca man carrying a bag of ceramic objects on his back

The

Muisca people were deeply embedded in a vast and sophisticated trade

network that extended well beyond their highland heartland—including the

area around present-day Raquira. While they are best known for their

salt, emeralds, and goldwork, ceramic objects were also part of this

exchange system, especially as containers, ritual items, and trade goods

in their own right.

-

Raquira and the surrounding Boyaca region offered abundant clay

deposits, which the Muisca skillfully transformed into hand-built

pottery—vessels, bowls, and ceremonial urns often decorated with

geometric motifs. These ceramics were not only used locally but also

traded with neighboring cultures such as the Guane, Panche, and Muzo

peoples. In return, the Muisca acquired tropical goods like cotton,

feathers, fruits, and dyes from lower-altitude regions.

-

The Muisca didn’t use wheeled transport or pack animals, so trade was

conducted via human porters along well-established footpaths that

crisscrossed the Andes. These routes connected highland settlements

like Raquira to distant valleys and lowlands, making the Muisca a key

link in the pre-Columbian trade web of northern South America.

-

Their ceramics, while not as ornate as their goldwork, carried

cultural and symbolic value—especially in ritual contexts. Some pieces

have been found in burial sites far from their origin, suggesting they

were valued beyond their utility.

|

|

Fountain with a boy peeing in the square in front of the church

|

|

Facade of the Iglesia San Antonio De La Pared

The facade of

the Iglesia San Antonio de la Pared in Raquira is a striking blend of

colonial and Gothic architectural styles, reflecting the town’s rich

religious and cultural heritage.

-

Built in 1600 by the master builder Cristóbal Aranda, the church was

designed based on plans by Luis Enríquez and later refined by

architect Father Cayetano García Tolosa.

-

The exterior is modest yet elegant, with a symmetrical layout and a

central bell tower that rises above the main entrance.

-

The facade is typically painted in earthy tones that harmonize with

Raquira’s colorful aesthetic, and it features arched doorways and

windows that echo the Gothic influence.

-

While not overly ornate, its charm lies in its simplicity and the way

it integrates with the town’s artisanal character.

|

|

Church interior

The interior of the Iglesia San Antonio de

la Pared in Raquira preserves a colonial aesthetic that reflects its

17th-century origins.

-

Built in 1600, the church maintains a simple yet reverent atmosphere,

with wooden altars and religious iconography that speak to centuries

of devotion.

-

The architectural style inside is consistent with the colonial-Gothic

fusion seen on the exterior.

-

Expect vaulted ceilings, arched windows, and a layout that draws the

eye toward the altar.

-

The materials—primarily wood and stone—give the space a warm, grounded

feel, and the lighting is typically soft, enhancing the contemplative

mood.

-

This church isn’t just a historical monument—it’s a living part of the

community. Locals gather here for major religious festivals like the

Romería de la Candelaria in February and the patronal feast of San

Antonio in June.

|

|

Altar of Saint Anthony of Padua

-

The angel in blue holding a chalice represents divine sacrifice and

the Eucharist. The chalice is a powerful symbol of Christ’s Passion

and the sacrament of Communion. Its presence beside Saint Anthony may

highlight his deep devotion to the Eucharist and his role as a

preacher of Christ’s love and sacrifice.

-

The angel in pink holding a palm symbolizes martyrdom and spiritual

victory. While Saint Anthony himself wasn’t a martyr, the palm may

represent his triumph over worldly temptations and his saintly

virtues—especially humility, purity, and charity.

-

Together, these angels frame Saint Anthony as a figure of

contemplation and spiritual triumph: one who embraced the mystery of

the Eucharist and lived a life worthy of heavenly reward. The

colors—blue for divinity and contemplation, pink for joy and

resurrection—further reinforce this dual message of sacrifice and

glory.

|

See Also

Source

Location

Convent of the Holy Ecce Homo

Monquira Archaeological Park

El Fosil Community Museum

El Recreo Ecotourism Farm

Villa de Leyva