The Gold Museum in Bogotá—Museo del Oro—is one of Colombia’s most dazzling cultural treasures. Located in the heart of the capital, it houses the largest collection of pre-Hispanic gold artifacts in the world, with over 34,000 gold pieces and thousands more in pottery, stone, shell, and textiles.

What makes this museum truly special is how it brings to life the beliefs and artistry of Colombia’s indigenous cultures. Gold wasn’t just a symbol of wealth—it was sacred. Many communities believed it held spiritual power, and the museum’s exhibits reflect that reverence.

Among its most iconic pieces is the Muisca Raft, a golden sculpture that inspired the legend of El Dorado. It depicts a ritual in which a chieftain, covered in gold dust, offered treasures to the gods in the middle of a lake—a story that lured countless explorers into the jungle in search of mythical riches.

The museum is beautifully curated across multiple floors, with interactive exhibits, an auditorium, and even a café and gift shop. It’s open Tuesday to Saturday from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

|

Distribution of the museum collections across the building's

floors

|

|

Metalworking «Metallurgy is one of humanity's greatest achievements. Since its beginnings some 9,000 years ago in the Near East, metalworking transformed societies and community life. When humans discovered the malleability, hardness, and resistance of copper, iron, and their alloys, they made tools, weapons, and utensils; when they marveled at the beauty of the color and shine of gold and silver, and the immutability of the golden metal, they used them to create symbols that legitimized their rulers and recreated their gods. Metallurgy was invented at different times in different places around the world. Independent and diverse metallurgical developments emerged in Anatolia, China, the Great Lakes region of North America, and the Central Andes. Some, such as in South America, spread over vast territories. The art of goldsmithing arrived from the south to Colombia 2,500 years ago. The ancient goldsmiths of this region continued the tradition of experimenting with gold, copper, and their alloys, and invented or perfected various techniques, such as lost-wax casting and granulation soldering. They even discovered how to work platinum, a metal that could only be used in Europe in the 18th century due to its high melting point.» |

|

Fotuto (conch trumpet) «Sometime in the early centuries AD, during the Yotoco Period, between 200 BC and 1300 AD, a goldsmith from the Calima region of the Cauca Valley pressed seven thin sheets of gold onto a sea snail. The careful folds and the small staples held together are still visible. The natural shell deteriorated, but the gold retained its form: an extraordinary synthesis of nature and culture. This is a fotuto, a conch trumpet: what an extraordinary symbol to begin this room, where metal extracted from rivers becomes ornaments that symbolize the power to summon and unite the community around the caciques, just as the fotuto summons people to meetings, celebrations, and rituals.» |

|

Crown «This crown was made by hammering high-quality gold. The hammered embossed and cut-out hanging figures were assembled using rings.» |

|

Pins «Pins carved from deer bones and partially coated in sheets of gold.» |

|

People and Gold in Pre-Hispanic Colombia «The Americas were settled 20,000 years ago by hunters and gatherers from the Old World. After occupying this territory, they eventually developed agriculture and lived in villages and cities. Metallurgy, discovered 3,500 years ago in Peru, spread to the southern coast of Colombia. From 500 BC until the Spanish conquest, metalworking flourished in the Andean and coastal areas. Thousands of objects were crafted in various metals in more than a dozen different styles. Metalworking was common among societies with permanent political and religious leaders who ruled over groups of villages. Although not state-based, these chiefdoms supported their large populations with efficient agriculture, centered on the cultivation of corn or cassava, and a good supply of game and fish. Thanks to the food surpluses, some people dedicated themselves to specialized activities, such as mining and goldsmithing. Metallurgical production served rulers, who used it to enhance their prestige and make their authority visible. These sacred and symbolic objects expressed a complex philosophy that addressed the origin of the world and humanity, explained the evolution of the universe, and justified social and natural relations. Common people used numerous simple ornaments. Metals were also used to make tools and offer things.» |

|

Nariño «In the cold Andean highlands and valleys of the department of Nariño and northern Ecuador, societies of farmers, shepherds, and merchants lived from 400 to 1600 CE. Two different types of grave goods have been found in the deepest tombs in the Americas, with sumptuous emblems of power, suggesting that two groups of rulers coexisted. Indeed, many Andean societies had a dual social structure and way of thinking, symbolizing complementary opposites of nature and the cosmos: masculine and feminine, sun and moon, above and below, night and day, cold and heat. When the Conquest came in 1550, the Quillacingas (Moon-nosed) people lived in central and northern Nariño, on hillsides and flat areas. They placed oval-shaped slabs on the skulls of some of the dead as offerings. To the south were the Pastos, in densely populated villages on hilltops; their pottery depicts scenes of fishing, hunting, and herding. Their descendants maintain some of their customs and traditions.» |

|

Pectoral |

|

Top: Nose ring Bottom: Nose ring |

|

Top: Diadem Bottom: Nose ring |

|

Rotating disk |

|

Bell |

|

Left: Nose ring Right: Nose ring |

|

Left: Pectoral Right: Pectoral |

|

Pectoral |

|

Tumaco «In the floodplains and mangroves of the Pacific Coast, between Esmeraldas in Ecuador and Buenaventura in the Cauca Valley, societies of fishermen, farmers, seafood gatherers, and hunters who navigated the sea and worked with metals lived for a thousand years, between 700 BCE and 350 CE. They extracted gold and platinum from river sands, which they transformed into small and delicate ornaments such as pendants, headbands, and nose rings... or into fishhooks. They built their homes on artificial platforms to protect them from flooding. Ceramic human figures are found decapitated in garbage dumps, burials, and near the sea, as if they had been broken in a ritual. They have ornaments inserted into the skin, ear and nose rings, and cranial deformities, symbols of social rank. Scenes of motherhood, eroticism, illness, and old age are depicted. The chieftains, represented in large and ornate ceramic figures, directed economic and ceremonial life.» |

|

Rectangular homes «Ancient Tumaco - La Tolita communities built rectangular homes with gabled roofs on islets surrounded by mangrove swamps, on artificial platforms to protect them from flooding.» |

|

Faces in ceramics «The human figure was represented with marked cranial deformations and numerous ornaments inserted into the skin. Many were discarded in garbage dumps, decapitated, as if they had taken part in a ritual.» |

|

Jaguar and puma «In Amerindian thought, the jaguar and the puma symbolize masculine power and strength, as well as the skill and sagacity of the hunter and the warrior.» |

|

Calima «The hills of the upper and middle Calima River and the flat Cauca River in the Cauca Valley hold vestiges of nearly 9,000 years of settlement. The ceramic vessels of farmers from the Ilama Period (1500 to 100 BCE) depict the physical appearance of people and their daily activities. Fabulous, mythical beings, combining human, feline, amphibian, bat, and serpent traits, seek to appropriate the strength, audacity, ferocity, and agility of these animals. A funerary trousseau from the Yotoco Period (200 BC to 1200 AD) links the chief who wore it with felines. A repeated, enigmatic, and iconic face expressed values and beliefs and supported the power and rank of leaders. In the Malagana cemetery (200 BC to 200 AD), masks resembling skulls or lifeless faces were superimposed over the dead. The burials of figures from the Sonso period (650 to 1700 CE), in sarcophagi with harpoons, spears, and palm darts, contrast with those of earlier periods.» |

|

Fabulous beings «Fabulous beings, probably mythical ancestors or transformed shamans, combine human traits with feline, frog, bat, snake, turtle and bird. In some, the legs, arms and hair are serpents.» |

|

Gold funeral mask «Masks in the form of skulls or lifeless faces were placed on the dead person, one on top of the other. Most Malagana goldwork was made for funerary regalia.» |

|

Feline regalia «This regalia, which was found in a Yotoco-period tomb, related its owner to feline figures and their power. The circular plates on the nose ring imitate the jaguar's spots, and the prolongations, his limb.» |

|

Ornament «Ornaments that produce a play of sounds and reflections of light.» |

|

Luxury object «Luxury objects were used and worn by leaders as symbols of their political, economical and ritual dominance over their community. When they died, these objects were buried with them.» |

|

Figurine «Yotoco-period funerary regalia consisting of circular ornaments and figurines. The figurines of men and women are adorned with finery and headdresses reminiscent of the statues at San Agustin.» |

|

Yotoco icon «The Yotoco icon symbolized ideas of cosmology, and these lent support to the power of whoever exhibited it. The impassive face transmits the idea of a stable, powerful leader.» |

|

Poporos «The poporos, which are containers that held the lime that was used when coca leaves were being chewed, are shaped like humans, birds, jaguars and alligators, or vegetables such as corn or pumpkins.» |

|

Sticks for removing lime from poporos «The masked figures on the sticks that were used for removing lime from poporos represent dancers in rituals which restated the community's social, political and religious links.» |

|

Kneeling female figures «Kneeling female figures, with quarts beads inside, were found on archaeological digs near ancient housing sites. They were offerings to stimulate fertility.» |

|

San Agustín «In the mountainous regions of San Agustín and the La Plata Valley, at the headwaters of the Magdalena River, small societies of the Formative Period saw the emergence of social hierarchies beginning around 1000 BCE. During the Regional Classic Period, between 1 and 900 CE, the rank and religious power of leaders were manifested in the construction of funerary monuments with stone statues carved from volcanic tuff. Although the use and accumulation of goldsmith ornaments were not common among these leaders, some were buried with grave goods containing gold objects. The gracefulness of a winged fish contrasts with the imposing statues. During the Recent Period, from 900 to 1500 CE, the population increased and continued to live in the same villages, under new leaders who based their power on economic control. Tombs from the Recent Period contain only vessels for domestic use.» |

|

Anthropomorphic statue |

|

Gold Pendant «Gold objects were not abundant in the Regional Classic period. However, regalia with attractive ornaments were found, such as a winged fish and a pendant in the shape of a statue.» |

|

Tierradentro «The Spanish called the mountainous knots and deep canyons of northeastern Cauca Department "Tierradentro," where they felt enclosed by the mountains. Farmers and pottery-making societies lived there from as early as 1000 BCE. From the Middle Period (150 BCE to 900 CE), grave goods containing luxurious metal objects were found in shaft tombs with side chambers. In contrast to the rich grave goods, other tombs contained few ceramic vessels. However, secondary burials are better known in underground burial chambers or hypogea carved into mountaintops with shapes reminiscent of the dwellings of the living. Ceramic urns containing the exhumed bones of one or more individuals were placed in these tombs. Medium-sized anthropomorphic statues with naturalistic features and expressions were also carved. The current Paeces indigenous people arrived in Tierradentro after the Conquest.» |

|

Zoomorphic Alcarraza «Different types of Middle period burials are known, some of them accompanied by one or more pottery vessels, such as three-legged pots that were used for cooking.» |

|

Gold Bracelet «The special nature and excellent quality of the objects making up the regalia found at Rio Chiquito, Cauca, show that leaders reinforced their prestige through the use of luxury goods.» |

|

Anthropomorphous statue «Anthropomorphous statues were carved out of volcanic rock at Tierradentro, but these were smaller than the ones at San Agustin, with naturalist features and expressions.» |

|

Tolima «In the warm middle valley of the Magdalena River and on the slopes of the Central and Eastern mountain ranges, in northern Huila and Tolima, traces are found left 16,000 years ago by groups dedicated to hunting, fishing, and gathering. Later, fish, lizards, crickets, and fantastical beings combining features of several species were cast in gold. Symmetrical pendants evoke humankind in varying degrees of schematization, while humans, bats, and felines merge in a continuum of transformations. In a pectoral found in Calarcá, Quindío, the human body is limited to two dimensions and framed in multiple symmetries, brought to life by the use of brilliance and the skillful interplay of decorative motifs. The backs of funerary chairs show the schematized human figure surrounded by amphibians and reptiles. In Suárez, Tolima, a shaft tomb was excavated whose shell and clay objects indicate that gold was not the only emblem of power and hierarchy.» |

|

Insects and small animals cast in gold «Insects and small animals cast in gold, sometimes fantastic, sometimes naturalistic. They are jaguars, fish, birds, lizards and crickets, or combinations of various species.» |

|

Man transformed into a bat and jaguar «When he is transformed into a bat and jaguar, man evokes and merges the powers, knowledge and habits of these two animals, and reveals the secrets of life and death.» |

|

Shamans healing the sick «The shamans of numerous present-day indigenous groups heal the sick by rhythmically stirring palm leaves, just as this person seems to be doing.» |

|

Quimbaya «For two millennia before the Conquest, Middle Cauca was populated by farmers, gold and salt miners, ceramists, and goldsmiths. Goldwork from the Early Period (500 BCE to 600 CE) displays iconic figures of leaders, both male and female, as symbols of identity. The colors, luster, and shapes of gourds, squashes, calabashes, and women alluded to fertility. A poporo, or lime container, is particularly notable, shaped like a high-ranking woman in a ritual pose. The Late Period (800 to 1600 CE) saw profound changes, great cultural diversity, and an increase in population. People painted their bodies, wore beaded ties on their limbs, and inserted ornaments into their noses and under their mouths. Goldsmithing, which used copper extensively, and pottery became geometric and schematic. With their ornaments and paintings, the chieftains resembled jaguar-men, frog-men, and lizard-men. Around 1540, due to differences in customs and language, the Europeans classified the indigenous people into "provinces": Caramanta, Anserma, Arma, Picara, Carrapa, Quimbaya, Quindo, and others. The majority were wiped out during the conquest.» |

|

Poporo (container for lime) |

|

Gold figure «Iconic figures of both men and women, naked, with half-closed, almond-shaped eyes and body paint, and wearing ornaments and ligatures, were symbols of some kind of social identity among these groups.» |

|

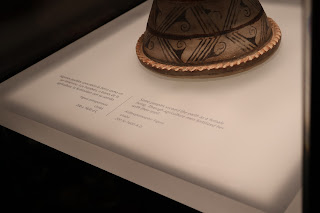

Gold crown «Hammered gold or tumbaga helmets or crowns were the leaders' largest and most visible emblems.» |

|

Cauca goldwork «Cauca goldwork, produced after 900 CE, in the Popayan valley and surrounding area in the central range. Little is known about the people who made it.» |

|

Pectorals «The conquistadors told how the chieftains in this region lived in big houses surrounded by palisades, where they kept images and desiccated bodies of their enemies, and engaged in cannibalism rituals.» |

|

Center: Gold pectoral «The chiefs wore a loincloth as long as a tail, long nails as claws, and animal skins on their backs. On these breastplates, jaguar men, frog men, and lizard men represented the chiefs in their religious transformation into animal attire.» |

|

Pendant - Lizard |

|

Bird-men «In these ornaments, the bird-men wear twisted nose rings with circular ends instead of beaks; these are elements of bird transformation that allude to the shaman's ecstatic flight.» |

|

Zoomorphic pendant|Alto Cauca - Cauca, 900 CE - 1600 CE. 13,0 cm x 9,5 cm. «The combinations of birds, frogs, quadrupeds and humans reveal the importance of the idea of transformation in his symbolic thinking.» |

|

Pendant - Quadruped and Bird |

|

Pendant - Double animal |

|

Necklace |

|

Top: Annular nose ring

Bottom: Twisted nose ring |

|

Nose ring |

|

Zenu «Beginning as early as 200 BCE, farming chiefdoms built a hydraulic system that controlled flooding in the warm Caribbean plains for 1,300 years. The metaphor of weaving was present in the weave of drainage canals, fishing nets, pottery, and goldsmithing made from gold-rich alloys. Aquatic birds, caimans, fish, felines, and deer were both food resources and essential elements of their symbolic thought. The deceased were buried with clay figures of women and covered with mounds planted with trees from whose branches hung bells. The roundness of the mounds and pectorals signified gestation and rebirth. After 1100 CE, Until the Conquest, the Zenu retreated to the high savannas and the Sinu Valley, while related groups occupied the San Jacinto Mountains and the banks of the Magdalena River. The goldsmiths of the San Jacinto Mountains made mass-produced objects from copper-rich alloys: ear ornaments, pendants with dressed-up figures, and amphibian figures.» |

|

Nose ring |

|

Cane finial - Crustacean claw |

|

Cane finial - Pisingo duck |

|

Cane finial - Pisingo duck |

|

Cane finial - Spoonbill |

|

Right: Cane finial «"Some wear feathered hats... and at the head of all are the chiefs, the oldest in the middle... And to the chiefs they put totumas of chicha in their hands... and the pipers play very long flutes." Bartolomé Briones de Pedraza, 1540.» |

|

Cotton band with bells |

|

Pendants «During the Conquest, in 1530, the San Jacinto Mountains and the banks of the Magdalena River were inhabited by people culturally related to the Zenú. Similar themes can be seen in the pottery and ornaments of both societies.» |

|

Tairona «The northwestern Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta was inhabited by groups of goldsmiths, artisans, and builders during the Nahuange and Tairona periods. A tomb excavated in Nahuange Bay in 1922 identified the Tairona goldsmithing, characterized by the hammering of nose rings and pectorals in copper and gold alloys. From 200 CE, the people of the Nahuange period lived off fishing and farming in villages near the sea. During the Tairona period, from 900 CE to 1600 CE, the mountains were also colonized, and cities were built on stone foundations connected by roads. In 1514, the chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo wrote that the indigenous people of Santa Marta "had gold jewelry, feather headdresses, and elaborately painted mantles, with many carnelian, emerald, jasper, and other stones on them." Masks, in addition to ornaments, were used to transform into a bat-man, the most emblematic motif of the Tairona period. The bird in flight was a symbol of the power shared with other Chibcha language groups.» |

|

Pendant - Earwig |

|

Nose ring |

|

Nose ring |

|

Pectoral |

|

Anthropozoomorphic figure (Sitting on bench) «Masks and ornaments were used to transform shamans into bats; metal visors simulated the membranes of the ear, cylindrical nose rings raised the nose, and sublabial ornaments imitated the fleshy growth of the lower lip.» |

|

Zoomorphic Breastplate (with anthropomorphic figures) «The Tairona people of the Chibcha language shared the symbol of the bird in flight with other groups of the same linguistic family, such as the peoples of the Eastern Cordillera and lower Central America.» «This pectoral found in Guatavita is one of the masterpieces of Muisca goldsmithing. It has the body of a bird (wings and tail) and six bird heads, with their bodies, from whose beaks a small, hanging plaque shines. A Muisca creation myth, narrated by Spanish chroniclers such as Friar Pedro Simón, tells that at the origin of the world, two large black birds flew over the land, breathing a brilliant breath of light from their beaks: the world was thus illuminated and habitable. The present-day Uwas, incidentally, neighbors of the Muisca, maintain a similar myth, according to which the world was populated by the flight of scissor-tailed eagles. It is then understandable why, on this Muisca pectoral, eight priests seated in a basket-like position witness the origin of the world.» |

|

Pendant |

|

Pendant |

|

Pendant |

|

Muisca «Beginning around 600 CE, the Eastern Cordillera was gradually occupied by various peoples of the Chibcha linguistic family, native to Central America. In 1536, Europeans encountered the Muisca, Guane, Lache, Chitarero, and other groups, who maintained economic, ritual, and symbolic relationships and recognized each other as close relatives. Bird-man pectorals and ceramic mucuras indicate this shared worldview. Chibcha life was deeply imbued with religious precepts. Priests, called sheikhs, inhaled a hallucinogen to communicate with mythical beings, and restored the balance of the universe through offerings of figures of men, women, asexual beings, and scenes, a multitude of animals and everyday objects, which they placed in offering holders with human, animal, phallic, or hut-shaped figures. Even during the Colonial period, the bodies of important figures were preserved as mummies and placed in deep caves, wrapped in several layers of blankets, nets, and furs, with votive figures.» |

|

Beads |

|

Pectoral |

|

Earmuffs |

|

Mummy «The bodies of important persons were preserved for the afterlife and also to maintain their presence within the community. The mummies of chiefs remained in heir former residences and were carried out in processions. Many preserved bodies have been found inside deep caves.» |

|

Pectoral |

|

Offering figures or tunjos «Thousands of offering figures, or tunjos, differ in terms of alloy, colour, size, and details depicted. These characteristics were controlled, according to the message the offering was intended to transmit.» |

|

Votive group «This votive group appears to relate to two subjects: war - or hunting? - and the consumption of sacred plants in order to communicate with de gods. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal adhered to one of the tunjos revealed a date of around 1350 CE.» |

|

Human figures with an inset emerald «Human figures with an inset emerald are atypical, as is this offering vessel in the form of a quadruped with a long tail. They were found in a cave.» |

|

Votive figure (with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures) «A particular moment in Muisca religious life was also captured in small offering figures. In the so-called "gavia sacrifice," the victim, a sacred child brought from the Eastern Plains, where the sun rises, was tied to the top of a tall pole and shot with darts. His blood was collected in vessels and considered sacred.» «A post ending in a fork, and before it a person. This is a synthetic, miniature representation of a Muisca gavia or sacrificial post. In fact, the small human figure has a long shaft inserted into its chest, except that it is bent. The chiefs made offerings in the lagoons, as shown in the Muisca Raft, and with them made pacts with the levels of the cosmos below ours. In the gavia sacrifice, the blood of a sacred youth, the moxa (read: moja), brought from where the sun rises, the Eastern Plains, was offered, which probably signified a pact with the higher levels and with the Sun itself.» |

|

Uraba and Choco «The Uraba region offers multiple routes for travel and trade. Several millennia ago, it was a gateway for hunters and gatherers to South America. In the early centuries of the Christian era, the inhabitants of northern Colombia and lower Central America maintained contact, evidenced by their diverse goldsmithing, for example, in the spiral pectorals. Uraba goldsmiths crafted ornaments with female figures, poporos, and poporo neckpieces shaped like guaduas and calabashes, reminiscent of the goldsmithing of the Middle Cauca. Those from the Pacific region of Choco, rich in alluvial gold deposits, made schematic figures with staffs, feather ornaments, and masks, representing shamans in ritual attire.» |

|

Pendant |

|

Gold Pendant «On the Pacific coast in Choco, groups mined rich alluvial deposits of gold at different times, and produced goldwork. The conquistadors noted that the inhabitants of the Atrato wore nose rings, breastplates and ornaments under their lower lips.» |

|

Female figures «The potters and goldsmiths of Uraba depicted women's ornaments, paint and clothing on female figures. Those made of gold were used for bodily decoration, while the pottery ones were used in rituals and as funerary offerings.» |

|

Pendant «Pendants in the form of birds, feline figures, frogs and bird-headed quadrupeds reproduced both the natural and the mythical wildlife. Two, three and even more figures were often found joined together.» |

|

After Columbus... «In 1492, two continents long cut off from communication discovered each other. Wars of conquest and disease decimated the indigenous population, which was then subjected to colonial tribute in agricultural labor, transportation, and mining. Many objects were melted down in response to the mercantile concept of gold and a new religion. Since the 19th century, vestiges of the past have motivated the study of the ancient history of this territory.» To this day... «Colombia has a history spanning 15,000 years. Pre-Hispanic societies left us a valuable legacy of diverse organizational forms, adaptations, and ways of thinking. Currently, there are 84 indigenous groups that speak 64 aboriginal languages. Most maintain their religion, and some use gold inherited from their ancestors in their rituals. Pre-Hispanic objects are the heritage and identity of Colombians. Its ancestral message of diversity and respect for difference points to the future in a country that has combined African and European influences with its indigenous culture.» |

|

Cosmogony and symbolism «Cosmologies placed society and its environment within the universe. All things acquired a place and meaning, and were intertwined in profound symbolism. Myths told that at the beginning of time, the creators gave people what was necessary for life. The Cosmology and Symbolism room houses several of the master objects from the collections of the Gold Museum of the Banco de la República—incidentally, inside a secure vault. But the value preserved here is that of the indigenous thought that gave meaning and purpose to these magnificent objects. We cannot know exactly what societies of millennia ago thought, and surely, as is the case among indigenous peoples today, there was great variety in their ways of conceiving the world and existence, in their cosmologies. However, among present-day Amerindian peoples, there are similarities in the forms and contents of symbolic thought. There are also encounters between the symbolism of Indigenous people today and the objects of their ancestors from 500 to 2,000 years ago. We invite you to explore other realities, alien to Western thought and no less logical for that, as they respond to different experiences of relationship with the environment and to their own life processes.» |

|

Images of the Cosmos «Pre-Hispanic cosmologies narrated the origin, evolution, and structure of the universe; they assigned a place and meaning to all beings and established an order in their relationships. Among some societies, the cosmos was represented as consisting of several superimposed, connected, and interdependent levels or worlds; certain colors, smells, animals, plants, and spirits were associated with them. The universe manifested itself in a visible, material dimension and in a spiritual dimension, powerful and hidden from most people. According to numerous American cosmologies, the universe was made up of three worlds. Humans inhabited the intermediate world, while gods, ancestors, and other supernatural beings resided in the upper or underworld. The upper level and the underworld were conceived as having opposite and complementary characteristics, such as light/dark, masculine/feminine, dry/humid. The middle world, that of the people, combined elements of the other two. Goldsmith societies classified fauna, flora, and other beings into categories based on various principles such as form, habitat, food, and cultural use. They captured these taxonomies in their objects. Birds symbolized the upper world. People, jaguars, and deer personified the middle world. The lower levels were represented by bats, alligators, snakes, and other inhabitants of the holes in the earth. Among Amerindian peoples, society is conceived as united with nature. People, animals, plants, and spirits form a great cosmic society in which they maintain relationships identical to those of humans.» |

|

Zoomorphic sex cover «According to numerous American cosmogonies, the universe was made up of three worlds. Mankind lived in the intermediate world, whereas gods, ancestors and other supernatural beings resided in the upper world or the underworld.» |

|

Cane finial «The upper world and the underworld were conceived as having opposing and complementary characteristics, such as light/dark, male/female or dry/wet. The middle world, where people lived, combined elements from the other two.» |

|

«Birds symbolized the upper world. People, jaguars and deer personified the intermediate one, while the lower levels were represented by bats, caimans, snakes and other creatures which inhabited openings in the earth.» |

|

Zoomorphic pendant «The coroncoro, or cucha, is a triangular-bodied fish with a striking black and white pattern on its scales, which the goldsmith depicted on this pendant. Bearded, it swims along the bottom of the water in search of food. What's most notable, however, is that when it's trapped because the marshes in the Momposina depression dry up, it walks on the mud, singing its hoarse singsong, until it finds open water.» |

|

«A leading figure with a fan headddress, the Sun, on a bar carried by figures makes the journey between the solstices. Bats from the underworld can be seen underneath or at his sides.» |

|

«Goldworking societies classified flora and fauna and other beings in categories that were based on various principles, such as their shape, habitat, food and culture. They expressed these classifications in their objects.» |

|

«The cosmologies regulated hunting, fishing, sowing and other relations with animals, plants and the land, by establishing rules for ensuring a harmonious interaction with nature.» |

|

«Society is viewed by Amerindians peoples as being united with nature. People, animals, plants and spirits together form a great cosmic society where relations all are identical to those of humans.» |

|

The Symbolism of the Chiefs «A rich symbolism of taboos, objects, and ideas surrounded chiefs, caciques, and other dignitaries. They were considered descendants of divinities and associated with powerful beings such as the jaguar. It was forbidden to look at their faces, and their feet were often not allowed to touch the ground. They had several wives, servants, and large houses surrounded by palisades. They were always carried on litters, and only they wore certain adornments or ate certain foods. When they died, they were mummified and placed in large tombs or within their enclosures, which from then on became sanctuaries. Emeralds, macaw feathers, seashells, resins, and other foreign goods gave the chiefs prestige. They arrived from distant, unknown, and mythical places through long chains of exchange. Gold was associated with the sun for its color, intense brilliance, and immutability. Golden ornaments expressed the celestial and divine origin of the rulers' power. Chiefs used body postures and gestures different from those of their subordinates. The meanings of these postures and gestures manifested their connections with higher beings and levels. By covering themselves with gold, the chief appropriated the seminal and procreative forces of the sun. They embodied the powers of this deity of the upper world on this earth. In some societies, chiefs and captains, upon completing their long training in special temples, could have their noses and ears pierced to wear nose rings and ear ornaments.» |

|

Anthropomorphic figure «Emeralds, macaw feathers, sea shells, resins and other foreign items gave the chieftains prestige. These arrived from distant places that were unknown and mythical, via long barter chains.» |

|

Nose ring «Because of its colour, intense shine and unchangeability, gold was associated with the sun. Gold ornaments expressed the celestial, divine origin of the rulers power.» |

|

Anthropomorphic figure «Chieftains adopted postures and gestures that differed from those of their subalterns. The meanings of these postures and gestures expressed their links with superior beings and levels.» |

|

Votive Figure (With anthropomorphic figures) «A votive object in the form of a fence with the figure of a two-headed man carrying a forked staff. The staff, with one face down and then two faces, seems to explain: a unit is always composed of two parts. Dualism, a worldview that seeks balance between the masculine and feminine forces of the cosmos, was present in Muisca religion and also in politics. The chronicler Fray Pedro Simón mentions that the figures in Muisca temples, which he calls "idols," were always a pair. Although the conquistadors only saw one chief in each Muisca village, after having killed the Zaque of Tunja in an ambush, for years Chief Ramiriquí-Tunja claimed to be the chief of Tunja as well. He was ignored.» |

|

Earring pendants «In some societies, chieftains and captains could pierce their nose and ears at the end of their long training in special temples, so they could wear earrings and nose rings.» |

|

Top: Zoomorphic Votive Figure «The deer was a sacred animal for various groups, and it was believed that when some people died, they were transformed into deer. Eating venison was a privilege that was enjoyed by the rulers.» «A deer in a Muisca artist's excellent rendering. It's not flat, but three-dimensional: the goldsmith carved its shape from a core of clay and charcoal before coating it with the wax that would be replaced by the metal in the foundry. Over the wax, using a needle or thorn, he drew some motifs: these are the same ones the Muisca priests drew "with a brush," according to Bochica's teachings (as Spanish chroniclers say), on the cotton fabrics that thus acquired the greatest symbolic value among the Muisca. Receiving a painted blanket from a chief was the greatest honor that could be bestowed upon a Muisca. And listen to this curious thing: blanket was called Bo, and deer, Chihica. This object seems to be telling us: Bochica.» |

|

Chieftain covered in gold «When the chieftain covered himself in gold, he appropriated the seminal, creative powers of the sun. He embodied on earth the powers of this deity from the upper world.» |

|

The Body-Clothing and Transformation «In many Amerindian worldviews, there is no radical difference between humans and nonhumans. People, animals, plants, rocks, and objects are people; different types of people, endowed with a soul or spirit. Tapir people, fish people, and others live in communities, harvest crops, have their homes, and dance like humans. Each type of people has a particular way of seeing the world, a perspective determined by their body, a body-clothing that can be removed and changed at will. Wearing feathers, adorning oneself, or painting oneself means changing one's body-clothing and thus transforming one's perspective on the world. A person dressed in the attire of animals, ancestors, or mythical spirits incorporated the names, abilities, and characteristics of those species or beings. Bird-women, vampire-men, and snake-men reveal a universe of transmutations. Transformed into a vampire-man, the person saw the world upside down; As a bird-woman, she transcended other dimensions of the cosmos. With a "second skin" composed of ornaments, paintings, and clothing, the dancers entered another reality and time. They perceived the world through the eyes of a crocodile, a hummingbird, a plant, an ancestor, or a divinity. By transforming into birds such as condors, eagles, toucans, and parrots, they acquired colorful beaks and plumage, as well as extraordinary abilities: high flight, keen vision, and hunting prowess. According to ancient myths, at the beginning of time, black birds, ancestral shamans, brought light to the earth in their beaks and gave their territories to the first clans. The priests and shamans, some seen as genuine bird-men, performed magical flights across the universe. Their paraphernalia of bird figures gave them the power to undertake these long journeys. Some societies taught parrots to speak, sometimes replacing sacrificial victims with them. For these groups, language transformed these birds into humans.» |

|

«A person decked out in the attire of animals, ancestors or mythical spirits thus incorporated the names, abilities and characteristics of these species or beings.» |

|

«Bird-women, vampire-men and snake-men reveal a universe of transformations. When transformed into a vampire.man, the person observed the world upside down; as a bird-woman, the person moved into other dimensions of the cosmos.» |

|

«With a "second skin" consisting of ornaments, paint and clothing, dancers entered a different reality and temporality. They perceived the world through the eyes of a crocodile, humming bird, plant, ancestor or divinity.» |

|

«By transforming themselves into birds like condors, eagles, toucans and parrots, they acquired not only showy beaks and plumage but also extraordinary powers: flying high, sharp eyesight, and hunting skills.» |

|

Pectoral |

|

Pectoral |

|

Earring pendant «Priests and shamans, some of them viewed as being genuine bird-men, made a magical flight through the universe. Their paraphernalia, with figures of birds, gave them powers to undertake long journeys.» |

|

«Some societies taught parrots to talk, so they could sometimes use them to replace sacrifice victims. According to their thought, language had transformed these birds into humans.» |

|

«According to ancient myths, a number of black birds, ancient shamans, brought light to the earth in their beaks at the beginning of time and gave the first clans their land.» |

|

The Jaguar Men «The jaguar was a symbol associated with religion and power since time immemorial in the Americas. Material evidence and texts reveal that high-ranking figures had names alluding to felines, wore elaborate attire made from their skins, painted their spots, and had long tails and claws. Their skulls were kept in temples while fierce feline images acted as guardians. Chronicles tell of chieftains and priests transforming into "big cats" and communicating with other jaguar spirits during ceremonies. The jaguar shaman saw his surroundings through feline eyes: other jaguars as humans and the people of his community as prey—a dangerous and fearsome situation for the people. The dignitary transformed into a jaguar acquired strength, agility, aggressiveness, keen vision, and cunning. With these, he acted to protect and heal his people or take revenge on his enemies. The feline collars and other adornments transformed the person into a true predator. He roared like thunder, snorted, and challenged with his claws, while his spirit roamed the forest in search of prey.» |

|

«When a dignitary was transformed into a jaguar, he acquired strength, agility, aggressiveness, sharp vision and astuteness. With these attributes, he protected and cured his people, or took revenge on his enemies.» |

|

Pendant - Jaguar |

|

«Necklaces and other feline ornaments transformed the person into a true predator. He roared like thunder, breathed heavily, and threatened with his claws while his spirit wandered through the forest in search of prey.» |

|

Plants of Knowledge «Pre-Hispanic societies cultivated a vast array of plants, some with important religious uses. Sacred plants such as tobacco, coca, yagé, yopo, and many others were used by shamans to delve into the spiritual dimension of reality and visit the other levels of the cosmos. The consumption of these plants, along with fasting, sounds, light effects, and repeated body movements, induced a trance state that made the invisible visible and taught the secrets and powers of the universe. Shamans and priests were experts in the processing and consumption of sacred flora, in their cultural uses, and in recognizing the different spirits encountered in trances. Aspiring priests were trained by ancient and wise masters. They spent years locked in temples and caves without seeing sunlight, subjected to diets without salt or chili, and many other restrictions. The shaman, under the influence of the power plants, connected the various worlds. He traveled through the middle world, the upper world, and the underworld to connect all his beings. Coca was used in rituals of divination, healing illnesses, and offerings. As a spiritual food, sacred plants were offered by humans to their gods. In the Andean region, coca Novogranatense or Colombian was cultivated. To maximize its stimulating effect, its dried leaves were mixed in the mouth with lime stored in the poporo. Yopo, a potent hallucinogen extracted from the Anadenanthera tree, came from the Eastern Plains. It was inhaled with a small spoon or a bird bone from trays decorated with animals that evoked the transformations experienced. A wide variety of bowls, spoons, inhalers, and trays were used to consume the different preparations of tobacco, yagé, yopo, and other plants of the gods.» |

|

«Shamans and priests were experts in precessing and consuming sacred plants, in the cultural uses of these, and in recognizing the different spirits they encountered in their trances.» |

|

«Candidates to the priesthood were trained by wise men and elderly masters. They spent years locked up in temples and caves, where they never saw the light of day and where they were subjected to diets without salt or chilis and to many other restrictions.» |

|

Pectoral |

|

«When the shaman was under the effects of plants that gave him power, he connected the various worlds. He journeyed through the middle, upper and lower worlds, linking all their beings.» |

|

«Coca was used in prediction rituals, curing the sick, and offerings. Sacred plants, as food for the spirit, had to be offered up by men to their gods.» |

|

«Coca novogranatense, or Colombian coca, was grown in the Andean Region. To optimize the stimulating effect, the dry leaves were mixed in the mouth with lime, which was kept in a poporo.» |

|

Yopo |

|

Hallucinogen tray |

|

«Yopo, a powerful hallucinogen that was extracted from the Anadenanthera tree, came from the Eastern Plains. It was inhaled using a small spoon or bird bone from trays with animals depicted on them that conjured up images of the transformations that were experienced.» |

|

«A wide variety of bowls, spoons, inhalers and trays was used when the different preparations of tobacco, yage, yopo and other plants of the gods were being consumed.» |

|

Myths and Rituals to Renew the World «Myths told the stories of the origin of the universe and culture in the distant past. They explained the genesis of the world, the stars, people, and animals, and how social groups acquired their territory, tools, musical instruments, and marriage rules. Rituals recreated mythology. Dancers, with their masks and attire, transformed themselves into creators or ancestors and, during the dances, relived the exploits of the earliest times; they brought the primordial past back to the present. According to an ancient tradition, the ancestral couple transformed into two serpents and returned to their lagoon of origin. This return to the setting and circumstances of the beginning is common in myths. The serpent with a head at each end appears associated with the sun as a symbol of its eternal oscillation between two opposite points on the horizon, a movement from which life sprang. Mythologies evoked unusual creatures such as multi-headed serpents or beings composed of various species: deer, snake, feline, and human. They were polymorphic ancestors, transformed shamans, or ancient heroes. On vessels depicting dancers wearing gruesome masks with prominent fangs and enormous jaws, the ancient Tairona depicted their temples transformed into primordial microcosms. Time was conceived as cyclical or spiral, modeling repeated events in nature such as the movements of the stars, animal reproduction, and women's periods. The metamorphoses of some animals, such as insects and amphibians, represented the incessant cycle of life, death, and rebirth to which all beings were subject. Flutes, maracas, and whistles reproduced the sounds of animals, founders, or ancestors. In rituals, music created the right atmosphere for entering into mythical time.» |

|

«According to an ancient tradition, the primitive couple were transformed into two snakes and returned to the lake where they had had their origin. This going back to the setting and circumstances of the very beginning is a common feature of myths,» |

|

«The snake with a head at each end appears associated with the sun, as a symbol of its eternal movement to and fro between two opposite points on the horizon. It was from this movement that life originated.» |

|

«Mythology conjured up images of strange creatures, such as snakes with several heads or beings made from various species: deer, snake, feline and human. They were polymorphic ancestors, transformed shamans or age-old heroes.» |

|

«Vessels depicting scenes of dancers wearing hair-raising masks showing prominent fangs and enormous jaws represented temples transformed into primordial micro-cosmoses.» |

|

«Time was conceived in a cyclical or spiral form, following the image of repeated events in nature such as the movements of the stars, the reproduction of animals, and the period of women.» |

|

«The metamorphosis that occurred in certain animals, such as insects and batrachians, represented the never-ending cycle of life, death and rebirth that all beings were subject to.» |

|

«Flutes, maracas and whistles reproduced the sounds of animals or the creators or ancestors. At rituals, music created an atmosphere that was conducive to getting immersed in mythical time.» |

|

Cosmogonic Technology and Artificers «Amerindian peoples also gave meaning to the materials, tools, and techniques of their technologies, and attributed special powers to goldsmiths and other transformers of matter. Materials were understood as life principles or beings in formation, which the artisans, with their work and the use of fire and their instruments, and in the manner of demiurges, helped to transmute or mature. Furnaces and crucibles were likened to wombs and other places of dangerous transformation; offerings and rituals were held in them to ensure the processes. Mirrors and other objects made of obsidian, pyrite, quartz, and metals were magical, divinatory, and prophetic instruments. Due to their reflective qualities, they were believed to communicate with supernatural worlds and beings. The symmetry and balance of the objects' shapes and designs expressed a concern for the search for a balance of properties and forces in the cosmos. A sacred philosophy of brilliance gave meaning to lustrous cultural objects and luminous natural phenomena. It generated a particular aesthetic by privileging certain materials and finishes. During ceremonies, the hanging plaques of the ornaments produced flashes of light and metallic sounds that favored the transformation of the participants and their communication with the gods. Reddish tones were frequently associated with blood, heat, transformation, and femininity; greens with regeneration, flowering, and vegetation; whites and yellows with semen and the sun. Silver and copper, with colors and surfaces vulnerable to the passage of time, were thought to be in concordance and harmony with the moon, the human embryo, and other changing and cyclical entities of nature. By extracting, processing, combining, and working metals, miners and goldsmiths simultaneously controlled and manipulated their material and spiritual properties. As creators and transformers, they were associated with the gods.» |

|

«Mirrors and other objects made of obsidian, pyrite, quartz and metals were magical, divinatory, prophetic instruments. Because of their reflective qualities, they were believed to communicate with supernatural worlds and beings.» |

|

Earring pendants |

|

Nose ring |

|

«Symmetry and balance in the shapes and designs of objects were an expression of the concerne to find equilibrium in the properties and forces of the cosmos.» |

|

Necklace «A sacred philosophy associated with shine gave meaning to glossy cultural objects and to luminous phenomena in nature. It led to a particular form of aesthetics by favoring certain materials and finishes.» |

|

Nose ring «During ceremonies, the hanging plates on ornaments twinkled in the light and gave off metallic sounds which helped transform those present and enabled them to communicate more easily with the gods.» |

|

Rotating disk «Reddish tones were often associated with blood, heat, transformation and female matters, greens with regeneration, flowering and vegetation, and whites and yellows with semen and the sun.» |

|

Earring pendants «Silver and copper, whose colors and surfaces were vulnerable to the passing of time, were thought to be in harmony with the moon, the human embryo, and other changing cyclical bodies in nature.» |

|

«When miners and goldsmiths extracted, processed, combined and worked metals, they controlled and manipulated the material and spiritual properties of those metals at one and the same time. As creators and transformers, they were associated with gods.» |

|

Anthropomorphic figure «Some peoples viewed the earth as a female being. Trough agriculture men fertilized her with their seed.» |

|

Vessel showing ritual scene «An intense communion with the universe and divinities was experienced at collective ceremonies, due to the ancient dances, the complicated and sumptuous costumes, and the moving music.» |

|

Anthropomorphic mark «Face paint and ornaments expressed the structure and functioning of society and the universe. They reminded people of life models that were suitable for them.» |

|

Trumpet «According to myths, the gods gave men musical instruments so their sounds could regenerate the world. They were sacred objects, which were only exhibited and used at certain ceremonies.» |

|

Anthropo-zoomorphous alcarraza (twin-spouted jug) «Complex representations of hybrid beings, mixtures of various species, conjured up images of important deities, ancestors, or cultural heroes in their cosmologies. They were used for teaching people the stories of these characters.» |

|

Anthropomorphic lime container «This sumptuously-attire female chieftain has adopted a solemn, engrossed attitude. Shamans, chieftains, potters and goldsmiths performed rituals to ensure that the cyclical processes of nature would continue.» |

|

Anthropomorphic breastplate «Priests and shamans who identified themselves with bats evoked this animal's habits in their own; they lived in dark temples, worked at night, and flew when they were in trances.» |

|

Lime container «Containers, small benches and other cultural objects were taken advantage of for representing the structure of the universe and the image of the land.» |

|

Anthropo-Zoomorphic breastplate «Because of its golden, shiny skin and its aggressiveness, astuteness and vitality, the jaguar was associated with the regenerative powers of gold and the sun.» |

|

Phitomorphic lime container «It was with lime container, which was found in Antioquia in the 19th century, that Banco de la Republica started its Gold Museum in 1939. It is an imitation of a gourd, the rounded features of which were associated with female body.» |

|

Phitomorphic lime container «Containers, small benches and other cultural objects were taken advantage of for representing the structure of the universe and the image of the land.» |

|

The Offering «The metal transformed by the goldsmiths returns to its place of origin. It takes the form of the bird-shaman who flies through the middle, upper, and lower worlds. It assumes the posture of the seated shaman who, in a hallucinatory trance, discovers the secrets of the cosmos and controls the forces that regulate life. The metal objects return to earth as gifts to the gods. Imbued with profound religious meanings, they are offered in lakes and caves to restore balance to the world. Thus closes the cycle of metal, which, manipulated by humans, serves to govern the universe.» |

|

The Basket man «Shamans adopt various postures during trances. Sitting with their arms clasped around their knees, they achieve states of concentration. Some indigenous groups call this posture "basket man," due to its resemblance to this container, and believe that apprentices store their masters' teachings there.» |

|

Communication with the spirits «The shaman flies to other dimensions of the cosmos to communicate with the spirits. He consults them about illnesses and the future, learns songs and dances, and trades fish and game with their "owners." Contact with the gods is his main source of wisdom and knowledge.» |

|

The shaman's attire «Shamans wear masks, feather crowns, and objects imbued with powers and meaning. Their maracas and rattles represent animals, heron feathers purify the body, and their figured staffs house the spirits who assist in rituals.» |

|

Birds, icons of the shaman «Birds are primordial symbols of the shaman. He shares the ability to fly with them. Like them, he sees great distances, connects the earth with the sky, and participates in the reproduction of nature. His crowns and other feather ornaments express this identification.» |

|

The shaman's helpers «Shamans rely on animal spirits and fantastic beings to assist them. Powerful birds like the sea eagle and the king vulture help them fly; voracious fish destroy diseases, and macaws and parrots carry their messages.» |

|

The Offering Raft «Every so often, the Muisca held grand ceremonies in the lagoons of the páramos. The villages gathered under the leadership of their chiefs and priests to make offerings to the gods. According to legend, on some of these occasions, the ritual of El Dorado was celebrated: a very powerful chief, accompanied by his priests, entered the middle of the lagoon on a raft and threw gold and emeralds into the water. The gold figure found in Pasca, Cundinamarca, seems to represent this tradition.» Running the Land «Guatavita Lake was the main center of religious offerings in the Muisca territory and the starting point of what the Spanish called "Running the Land": young people from the villages of the Savannah and the neighboring valleys would gather at dawn on its shores and set off at high speed along a path that led them to the lagoons of Guasca, Siecha, Teusacá, and Ubaque. At each of these sites, they would make offerings and then return, also running, to end up in Guatavita late at night.» |

|

Muisca raft «Votive figure depicting a ceremony possibly on a raft. It was made by a skillful Muisca metalsmith in the 14th or 15th century of our era.» |

|

«Votive figure in the form of a cacique carried aloft in a litter. It dates from the 12th or 13th century of our era.» |

|

The Offering Room of the Gold Museum «In the universe, natural and supernatural principles are in balance. There are men and women; shadow is followed by light, rain by drought, the wild is opposed by the domesticated, and the world above is opposed by the world below. When this balance is disrupted, chaos ensues; unstoppable forces take over the universe, terror roars, and disorder threatens. Then the wise men intervene to restore order to the world; through sacred offerings, they restore balance and allow life to continue its course. The mamos, or priests, of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta sing in the Offering Room. Gold is sacred to them, and they visit it to make offerings, as they also do at Laguna de Guatavita. Their ancestral music, called yanka, is accompanied by traditional instruments such as the seed rattle, the male and female conch shells, and the traditional drum. Entering the final exhibition hall of the Gold Museum, on the third floor, a dimly lit environment where six cylindrical display cases connect heaven and earth alludes to shamanic flight and the religious meaning of indigenous goldsmithing. The Muisca Raft, the object that symbolizes the myth and ceremony of El Dorado, introduces the theme of the offering made by the chief or shaman to promote or restore balance to the world. At the end of the tour, a person will stop you and tell you to wait. When a wall opens, you will witness a light and sound event that will remain etched in your memory. Neither the website nor the latest computer monitors can describe or convey what you will experience when you physically visit the Museum. Don't miss this opportunity to experience it! At the exit, the Reference Room offers visitors the opportunity to enjoy the video Poporo, created in 2004 by artist Luis Cantillo, inspired by the Museum's objects. This digital artwork received first prize at the IDB Video Art Biennial in Washington and second prize at the FILE 2004 festival in São Paulo, Brazil. You can also visit the Museum's website and use an app that will allow you to view the Muisca Raft and other objects in detail. Pre-Hispanic art objects never cease to amaze you!» |

See Also

-

Paloquemao Market

-

La Candelaria

-

Church of Our Lady of Candelaria

-

El Taller de Cocina

-

Santa Clara Church Museum

-

Primatial Cathedral of Bogota

Source

Location