The Church of St. Nicholas was built in 1530 by Prince Petru Rares and stands

as a significant example of Moldavian ecclesiastical architecture.

It is part of the group of Painted Churches of Northern Moldavia, which were

included in the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1993. The church was constructed

as a burial place for the founder and his family, and it reflects both the

spiritual aspirations and the artistic achievements of the time. Its structure

combines Byzantine and Gothic elements, with a harmonious layout that supports

its rich decorative program.

The interior of the church is renowned for its frescoes, which were completed

in 1532 and are considered among the finest in Moldavia. These paintings cover

the walls with scenes from the Bible, the lives of saints, and symbolic

representations of Christian teachings. Despite the passage of time, the

interior frescoes have retained much of their original vibrancy and detail,

showcasing the skill of the artists and the depth of theological thought

behind the compositions. The altar features a unique iconographic element—the

depiction of the sacrifice of Jesus during the proscomidia—which is rarely

found in Orthodox churches.

Although the exterior frescoes have suffered from weathering and are now

faded, the church remains a powerful testament to the religious and cultural

life of sixteenth-century Moldavia. Restoration efforts carried out between

1996 and 2000 helped preserve the structure and its artwork, ensuring that

future generations can continue to appreciate its historical and spiritual

significance. The Church of St. Nicholas at Probota Monastery stands not only

as a place of worship but also as a monument to the enduring legacy of

Orthodox faith and Romanian artistic heritage.

|

Fortress-like outer walls of Probota Monastery

The outer

walls of Probota Monastery in Romania are massive and fortress-like,

built to protect the monastic complex during the 16th century.

-

Erected under the rule of Petru Rares in 1530, these defensive walls

enclose the church, abbot's house, princely residences, and bell

tower, forming a secure compound typical of Moldavian civil

architecture.

-

Their robust construction reflects the turbulent times and the need

for spiritual sanctuaries to double as strongholds.

-

The walls are punctuated by towers that enhance their defensive

capabilities, and they remain among the few well-preserved examples of

medieval monastic fortifications in the region.

|

|

Monastery gate

In Orthodox Christianity, the monastery gate

is a deeply symbolic threshold between the secular world and the sacred

realm of spiritual devotion.

-

It marks the point where one leaves behind worldly distractions and

enters a space dedicated to prayer, asceticism, and communion with

God. This transition is not only physical but spiritual, echoing

biblical references to gates as passages to holiness and salvation.

The gate serves as a reminder of humility and reverence, preparing the

soul for the sacred experience within the monastery walls.

-

Beyond its symbolic role, the gate also functions as a place of

welcome and spiritual encounter. In Orthodox tradition, hospitality is

a sacred duty, and the gate becomes the first point of contact between

the monastic community and the outside world. It is where monks may

greet pilgrims, offer blessings, and extend kindness to strangers,

reflecting the belief that every visitor could be Christ in disguise.

Thus, the gate embodies both separation and connection, guarding the

sanctity of the monastery while inviting seekers into its spiritual

embrace.

-

the gatehouse is a striking feature of the fortified complex built in

the 16th century. It includes a vaulted passage and often a small

chapel above, reinforcing its role as a spiritual checkpoint. Passing

through this gate, visitors symbolically leave behind the concerns of

daily life and enter a space of contemplation and divine presence. Its

design reflects both the need for protection during turbulent times

and the Orthodox emphasis on spiritual transformation through sacred

thresholds.

|

|

St. Nicholas Church seen from the northwest

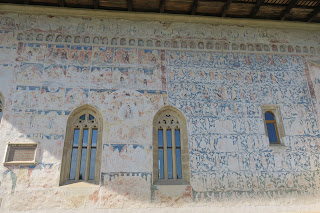

The north wall

of the Church of St. Nicholas is part of the exterior ensemble of

frescoes that once adorned the entire church.

-

Painted in 1532, these frescoes were created during the reign of

Prince Petru Rares and reflect the rich artistic tradition of

Moldavian religious art. Although many of the exterior paintings have

faded over time due to exposure to the elements, fragments of the

original compositions can still be discerned. The north wall, like the

others, was designed to convey biblical narratives and theological

themes to the faithful, serving both decorative and didactic purposes.

-

Among the remnants on the north wall are portions of the Akathist Hymn

and the Jesse Tree, which illustrate the lineage of Christ and the

veneration of the Virgin Mary. These elements were part of a broader

iconographic program that covered the church's exterior, making it a

visual catechism for worshippers. Despite the deterioration, the wall

retains traces of its former vibrancy and complexity, offering insight

into the spiritual and artistic aspirations of the time. Restoration

efforts supported by UNESCO have helped preserve what remains,

allowing visitors to appreciate the historical and cultural

significance of this sacred site.

|

|

Plate bell

The Church of St. Nicholas features a distinctive

bell made from a metal plate, a traditional element in Eastern Orthodox

monastic settings.

-

Unlike typical hanging bells, this flat metal plate is struck with a

mallet to produce a resonant sound that calls monks and visitors to

prayer or signals important moments in the liturgical day.

-

Its use reflects ancient practices where simplicity and durability

were valued, especially in remote or fortified monasteries.

-

The sound of the plate bell carries through the compound, serving both

practical and spiritual purposes by marking sacred time and

reinforcing the rhythm of monastic life.

|

|

Wooden board bell

At the Church of St. Nicholas, a

traditional wooden board bell known as a semantron is used to

call the faithful to prayer and mark liturgical moments.

-

This ancient instrument, made from a long plank of wood, is struck

rhythmically with a mallet to produce deep, resonant sounds that carry

across the monastic grounds.

-

The semantron predates metal bells in Orthodox tradition and

symbolizes the voice of the church, inviting spiritual reflection and

communal worship.

-

Its presence at Probota reflects the continuity of monastic customs

and the enduring simplicity of Orthodox liturgical life.

|

|

South wall

The south wall of the Church of St. Nicholas is

part of the renowned ensemble of frescoes that make the site one of the

most significant painted churches in Moldavia.

-

Though many of the exterior paintings have faded over time due to

exposure to the elements, the south wall still retains fragments of

its original decoration. These include scenes from the Akathist Hymn

and the Tree of Jesse, which were common themes in Moldavian church

art during the 16th century. The placement of these images on the

outer wall served both didactic and devotional purposes, allowing

pilgrims and passersby to engage with biblical narratives and

theological symbolism even before entering the church.

-

Inside the church, the south wall continues the visual storytelling

with vivid frescoes that depict biblical scenes, saints, and moments

from the life of Christ. These paintings were completed around 1532,

shortly after the church's construction under Prince Petru Rares. The

artistic style reflects Byzantine influences blended with local

traditions, characterized by expressive figures, rich colors, and

detailed compositions. The south wall, like the rest of the interior,

contributes to the immersive spiritual atmosphere of the church,

guiding worshippers through a visual journey of salvation history and

reinforcing the sacred function of the space.

|

|

Church seen from the southeast

The exterior wall of the nave

at the east end of the Church of St. Nicholas at Probota Monastery is

part of the celebrated ensemble of painted surfaces that once adorned

the entire church.

-

Although many of the frescoes have suffered from exposure to weather

over the centuries, the east end retains traces of its original

decoration. This wall traditionally features scenes related to the

Resurrection and the Last Judgment, themes that are central to

Orthodox theology and often placed on the eastern side of churches to

align with the rising sun and the symbolism of renewal and divine

light. The placement of these images was intended to inspire

reflection and spiritual awakening among those approaching the

sanctuary.

-

The frescoes on the east end of the nave were executed in the early

1530s, shortly after the church's construction under Prince Petru

Rares. They reflect the Moldavian style of painting, which blends

Byzantine iconography with local artistic traditions. Figures are

rendered with expressive gestures and vivid colors, and the

compositions are designed to convey theological narratives in a clear

and engaging manner. Even in their weathered state, the paintings on

the east wall continue to evoke the spiritual atmosphere of the church

and serve as a testament to the rich religious and artistic heritage

of the region.

|

|

Vaulted ceiling of the church portico

The portico vault of

the Church of St. Nicholas features a remarkable and unusual fresco

arrangement that sets it apart from other painted churches in Bukovina.

-

At the center of the vault is a depiction of the Father, enthroned in

majesty, surrounded by celestial imagery that emphasizes divine

authority and cosmic order. Flanking the Father on each side are the

twelve signs of the Zodiac, rendered with symbolic detail and arranged

in a circular rhythm that evokes the passage of time and the harmony

of creation. This celestial row serves not only as decoration but also

as a theological statement, linking the divine with the structure of

the universe and the unfolding of human history.

-

In most other churches of Bukovina, this row of Zodiac signs and the

image of the Father is typically placed at the top of the wall that

contains the Last Judgment scene, reinforcing the idea of divine

oversight and cosmic justice. However, at Probota, this iconographic

sequence is uniquely positioned on the portico vault itself, giving it

a more prominent and immersive role in the viewer's experience. This

placement invites reflection as one enters the sacred space,

suggesting that all who pass beneath it are stepping into a realm

governed by divine order and eternal truths. The artistic choice

reflects both theological depth and creative innovation, making the

portico vault a key feature of the church's spiritual and visual

narrative.

|

|

Panorama of the Last Judgment on the east wall of the church

portico

The Last Judgment in Orthodox Christianity represents the final

and eternal judgment by Christ of all humanity.

-

It is a central eschatological belief that emphasizes divine justice,

mercy, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. The icon of the

Last Judgment is not merely a depiction of future events but a

spiritual reminder of the moral choices each person must make. It

calls believers to repentance, humility, and vigilance, urging them to

live in accordance with the teachings of Christ. The image typically

includes Christ enthroned in glory, surrounded by angels, saints, and

the righteous, while the damned are shown descending into torment,

symbolizing the consequences of sin and separation from God.

-

Spiritually, the Last Judgment fresco serves as a visual theology that

encapsulates the entire Christian narrative—from creation to

redemption and final reckoning. It is often placed in a prominent

location within churches to confront worshippers with the reality of

divine judgment and the hope of salvation. The fresco is not meant to

instill fear but to inspire transformation and a deeper commitment to

spiritual life. It reflects the Orthodox understanding that salvation

is both a gift and a responsibility, and that every soul will

ultimately stand before Christ to account for its deeds.

-

At the Church of St. Nicholas in the Probota Monastery, the Last

Judgment is painted on the east wall of the portico, a placement that

differs from other Bukovina churches where it is usually found on the

west wall of the church. This fresco presents a vivid and detailed

vision of the final judgment, with Christ at the center, flanked by

angels and saints, and the souls of the righteous and the damned

moving toward their eternal destinies. The composition is rich in

symbolism, including scenes of resurrection, the weighing of souls,

and the separation of the saved from the condemned. Its location on

the east wall of the portico aligns with the rising sun, reinforcing

themes of resurrection and divine illumination.

|

|

Panorama of the entire Last Judgment, including the portico vault

|

|

Diagram of the Last Judgment

Diagram Legend:

- Father

- Zodiac

- Christ in glory (Deisis)

- Empty throne (Etimasia)

- Scale for weighing souls

- Weighing of souls

- River of fire

- Resurrection of the dead from earth

- Resurrection of the dead from the sea

- David playing a stringed instrument

- Peter leading the elect toward Paradise

|

|

Nave of the church

The nave in Orthodox Christianity holds

deep symbolic and spiritual meaning as the central space where the

faithful gather for communal worship.

-

It represents the earthly realm, positioned between the narthex, which

symbolizes the world outside, and the sanctuary, which signifies

heaven. This architectural arrangement reflects the spiritual journey

of believers, who move from the secular world toward divine communion.

The nave is often referred to as the ship of salvation, guiding the

congregation through the spiritual waters of life toward the kingdom

of God. Its openness and orientation toward the altar emphasize unity,

reverence, and the shared experience of liturgical life.

-

Spiritually, the nave serves as a place of transformation and

encounter with the divine. It is where the laity participate in the

sacraments, hear the Gospel, and engage in prayer and veneration. The

iconostasis at the front of the nave, separating it from the

sanctuary, acts as a visual and theological bridge between heaven and

earth, adorned with icons that invite contemplation and connection

with the saints. The nave's design, often enriched with murals and

sacred imagery, reinforces the idea that the church is not just a

building but a living space where heaven touches earth and the

faithful are drawn into the mystery of God's presence.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas, the nave is a richly decorated and

spiritually charged space that reflects the theological and artistic

traditions of 16th-century Moldavia. Its walls are adorned with

frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary,

and various saints, creating an immersive environment for worship and

reflection. The layout of the nave, with its orientation toward the

altar and its integration with the iconostasis, guides the faithful in

their liturgical journey. This sacred space embodies the monastery's

role as a place of prayer, teaching, and spiritual renewal, preserving

centuries of Orthodox devotion and artistic heritage.

|

|

Elijah's Ascent to Heaven

Elijah's Ascent to Heaven in

Orthodox Christianity is a powerful symbol of divine favor, spiritual

elevation, and the mystery of life beyond death.

-

Taken up in a fiery chariot, Elijah is one of the few biblical figures

who does not experience death, which signifies his exceptional

holiness and closeness to God. His ascent is seen as a foreshadowing

of Christ's Ascension and a promise of resurrection for the faithful.

It also reflects the belief that those who live in righteousness may

be lifted into divine presence, transcending earthly limitations

through grace and spiritual purity.

-

Elijah is also revered as a prophet who stood firmly against idolatry

and injustice, making his ascent a reward for his unwavering

commitment to God's truth. In Orthodox tradition, he is a model of

asceticism and prophetic courage, often associated with monastic

ideals. His fiery chariot represents divine energy and the

transformative power of God's will. The story encourages believers to

persevere in faith and reminds them that spiritual struggle leads to

divine union and eternal life.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas, the fresco of Elijah's Ascent is a

vivid and dramatic portrayal of this sacred event. The prophet is

shown rising in a chariot of fire, surrounded by flames and celestial

figures, capturing the moment of divine elevation with striking color

and movement. Positioned among other biblical scenes, this image

reinforces the church's role as a space for spiritual reflection and

theological teaching. It invites worshippers to contemplate the

mystery of divine ascent and the hope of eternal communion with God.

|

|

Pentecost

Pentecost in Orthodox Christianity is a profound

spiritual event that marks the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the

apostles, fifty days after the Resurrection of Christ.

-

It is considered the birth of the Church, when the apostles were

empowered to preach the Gospel to all nations. The event fulfills

Christ's promise to send the Comforter and reveals the fullness of the

Holy Trinity. The Holy Spirit, appearing as tongues of fire,

symbolizes divine illumination, transformation, and the sanctification

of humanity. Pentecost is celebrated as a feast of unity, mission, and

spiritual renewal, reminding believers of their calling to live in

communion with God and one another.

-

Theologically, Pentecost emphasizes the universality of salvation and

the dynamic presence of the Holy Spirit in the life of the Church. It

affirms that the Spirit continues to guide, inspire, and sanctify the

faithful, making the Church a living body of Christ. The icon of

Pentecost often shows the apostles seated in harmony, with the Holy

Spirit descending as a dove or flame, and a symbolic figure of the

world below them, representing the nations awaiting the message of

salvation. This imagery teaches that the Church is called to bring

light to the world, and that each believer is invited to receive the

Spirit and participate in the divine life.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas, the fresco of Pentecost captures this

sacred moment with vivid detail and theological depth. The apostles

are shown seated in a semicircle under an arch, with the radiant Holy

Spirit descending from above. Their expressions and gestures convey

reverence and readiness, while the architectural setting emphasizes

the sanctity of the event. This portrayal reflects the Moldavian

artistic tradition and reinforces the monastery's role as a place of

spiritual teaching and divine encounter. It invites worshippers to

contemplate the mystery of the Spirit and their own place in the

mission of the Church.

|

|

Three Warrior Saints

Warrior Saints in Orthodox Christianity

symbolize the union of spiritual strength and earthly courage.

-

Though many were soldiers in life, their sainthood comes from their

martyrdom and unwavering faith in Christ. They are revered not for

their military exploits but for their willingness to suffer and die

for the truth of the Gospel. Their armor and weapons, often depicted

in icons, are not signs of violence but of spiritual readiness,

representing the Christian's battle against sin, temptation, and evil.

These saints are seen as protectors of the Church and intercessors for

the faithful, embodying the virtues of bravery, loyalty, and divine

justice.

-

Spiritually, the Warrior Saints serve as models of vigilance and

sacrifice. Their presence in Orthodox iconography reminds believers

that holiness is not confined to monastic life but can be found in

every vocation, even in the midst of conflict. They stand as witnesses

to the power of faith to transform suffering into sanctity. Their

images, often placed prominently in churches, inspire the faithful to

remain steadfast in trials and to trust in divine protection. The

visual language of their icons—armor, swords, shields—speaks to the

inner struggle of the soul and the call to live with integrity and

courage.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas, the nave is surrounded by frescoes of

Warrior Saints, each depicted in ornate armor and bearing weapons that

symbolize their spiritual mission. Figures such as Saint George, Saint

Demetrius, and others stand in solemn contemplation, often gazing

toward Christ or the Holy Spirit. Their arrangement around the nave

creates a sense of sacred guardianship, as if the church is encircled

by heavenly defenders. This visual ensemble reflects the Moldavian

tradition of mural painting, blending theological depth with artistic

richness, and invites worshippers to see themselves as part of the

same spiritual struggle and divine protection.

|

|

Saint George (left) and Saint Demetrius (center) contemplating Jesus

Christ

Saint George and Saint Demetrius are revered in Orthodox

Christianity as powerful symbols of faith, courage, and divine

protection.

-

Saint George, known as the Victory-Bearer, is celebrated for his

unwavering commitment to Christ, even unto martyrdom. His image, often

shown in armor and mounted on a horse slaying a dragon, represents the

triumph of good over evil and the spiritual battle every Christian

must face. He is invoked as a protector of cities, soldiers, and the

faithful, and his feast day is marked with prayers for strength and

deliverance. Saint Demetrius of Thessalonica, likewise, is honored as

a martyr and military saint who defended the Christian faith during

times of persecution. His legacy includes miraculous interventions in

battles and healing, and he is seen as a guardian of the Church and a

model of steadfast devotion.

-

Spiritually, both saints embody the Orthodox ideal of the warrior for

Christ—those who fight not with hatred but with love, truth, and

sacrifice. Their presence in icons and frescoes serves to inspire

believers to remain firm in their convictions and to trust in divine

aid during trials. When depicted together, Saint George and Saint

Demetrius often exchange a glance or gesture that reflects unity in

purpose and shared contemplation of Christ. This visual dialogue

between them reinforces their role as intercessors and spiritual

brothers, standing before the Lord in prayer and vigilance. Their

armor and weapons are not merely symbols of war but of spiritual

readiness and the defense of faith.

-

In the Church of Saint Nicholas, Saint George and Saint Demetrius are

depicted side by side in a striking fresco that captures their

contemplative posture toward Jesus Christ. Saint George, on the left,

is shown in armor with his right hand raised in a gesture of

intercession, while Saint Demetrius, in the center, mirrors his stance

with a sword at his side. The two saints appear to be exchanging a

glance, united in their devotion and spiritual mission. A third

military saint stands to the right, possibly Saint Procopius or Saint

Theodore, completing the trio of defenders of the faith. The

inscriptions near their halos confirm their identities, and the

composition reflects the Moldovan tradition of mural painting, rich in

color and theological meaning. This portrayal invites worshippers to

reflect on the courage and holiness of those who serve Christ with

both heart and strength.

|

|

Archangel Michael (left), Archangel Gabriel (center), and the Mother

of God (right)

Archangel Michael, Archangel Gabriel, and the Mother of God each

carry deep symbolic and spiritual meaning in Orthodox Christianity.

-

Archangel Michael is honored as the leader of the heavenly hosts and

the protector of the faithful. He is often depicted in armor, wielding

a sword or spear, symbolizing divine justice and the triumph of good

over evil. His role in the Last Judgment and his presence in prayers

for protection reflect his status as a guardian of souls and defender

of the Church.

-

Archangel Gabriel, by contrast, is the messenger of God, known for

announcing the birth of Christ to the Virgin Mary. He represents

divine communication, purity, and obedience to God's will, often shown

holding a scroll or a lily to signify his role in revealing sacred

truths.

-

The Mother of God, or Theotokos, holds a unique place in Orthodox

theology as the one who bore Christ, making her the bridge between

humanity and divinity. She is venerated not only for her role in the

Incarnation but also for her ongoing intercession on behalf of the

faithful. Her image is often serene and prayerful, symbolizing

humility, compassion, and spiritual motherhood. She is seen as the

most exalted of all saints, and her presence in icons and liturgical

life reflects the Orthodox emphasis on her closeness to Christ and her

care for the Church. Together, these three figures embody protection,

revelation, and mercy, guiding believers in their spiritual journey.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas, these figures are depicted in a

striking fresco that showcases the Moldovan style of mural painting.

Archangel Michael stands on the left in full armor, symbolizing divine

strength. Archangel Gabriel is in the center, holding a scroll that

suggests a message from God. The Mother of God appears on the right,

also holding a scroll, possibly representing her intercessory prayer

or prophetic role. The Old Church Slavonic inscriptions beside their

halos confirm their identities and reinforce their sacred presence.

This trio forms a powerful visual and theological statement, welcoming

worshippers into a space of divine protection, revelation, and grace.

|

|

Saint Athenaios (left), Saint Nicetas (center) and Saint Callinicus

(right)

|

|

Saint Nicholas and Saint Athenaios

Saint Nicholas holds

profound symbolic and spiritual significance in Orthodox Christianity,

revered as a model of humility, generosity, and unwavering faith.

-

As Bishop of Myra, he became known for his acts of mercy and

protection, especially toward children, the poor, and the oppressed.

His life reflects the Gospel lived through action, embodying the

Christian call to love and serve others selflessly. Orthodox believers

see him not only as a historical figure but as a living intercessor,

whose presence continues to inspire compassion and spiritual devotion.

-

His legacy in Orthodox tradition emphasizes the virtues of kindness

and justice. Saint Nicholas is often portrayed as a defender of truth,

a miracle worker, and a guardian of the faithful. His feast day,

celebrated on December 6, is marked by liturgical services, charitable

acts, and prayers for his intercession. The saint's image, frequently

found in icons, reminds the faithful of God's mercy and the power of

holiness expressed through everyday deeds. His enduring popularity

across Orthodox lands reflects a deep spiritual connection that

transcends time and culture.

-

In Romania, the cult of Saint Nicholas is vibrant and deeply rooted in

both religious practice and folk tradition. He is celebrated as a

bringer of gifts and a moral guide, with customs that blend liturgical

reverence and popular rituals. At the Church of Saint Nicholas in the

Probota Monastery, his patronage is especially significant. The

church, built in the 16th century, is dedicated to him and serves as a

spiritual center where pilgrims honor his memory through prayer and

veneration. His presence there reinforces the monastery's role as a

place of divine protection and moral renewal.

|

|

Iconostasis in the nave of the church

The iconostasis in

Orthodox Christianity serves as a sacred partition between the nave and

the sanctuary, symbolizing the boundary between the earthly and the

heavenly realms.

-

It is not merely a physical barrier but a spiritual gateway, adorned

with icons that represent key figures in Christian theology. These

icons are arranged in a hierarchical order, guiding the faithful in

their contemplation and prayer. The iconostasis emphasizes the mystery

of the Eucharist, which takes place behind it, and invites worshippers

to engage with the divine through visual theology.

-

Spiritually, the iconostasis reflects the communion of saints and the

presence of Christ among the faithful. The central Royal Doors,

flanked by two Deacon's Doors, are used during liturgical services and

symbolize access to divine mysteries. The icons surrounding these

doors are not just representations but are considered to be

manifestations of the holy figures they depict. Through this

structure, the church teaches and inspires, offering a glimpse into

the heavenly liturgy and reinforcing the sacred nature of worship.

-

In the Church of St. Nicholas at the Probota Monastery, the

iconostasis is a remarkable example of Moldavian religious art. The

lower level features four main icons: on the far left is St. John the

Baptist, who looks toward Christ; to the left of the Royal Doors is

the Mother of God with the Child Jesus; to the right of the Royal

Doors is Jesus Christ, portrayed as Teacher and Judge; and on the far

right is Saint Nicholas, the patron of the church. These icons are

framed by three doors—the central Royal Doors and two Deacon's

Doors—each playing a role in the liturgical life of the church and

enhancing the spiritual symbolism of the iconostasis.

|

|

Leaving Probota Monastery

|

See Also

Source

Location

Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, Paiseni Monastery

Church of Saint George, Saint John the New Monastery