The Israel Museum is an art and archaeological museum in Jerusalem, Israel.

It was established in 1965 as Israel's largest and foremost cultural

institution, and one of the world's leading encyclopaedic museums.

It is situated on a hill in the Givat Ram neighborhood of Jerusalem, adjacent

to the Bible Lands Museum, the Knesset, the Israeli Supreme Court, and the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Archaeology Wing tells the story of the ancient

Land of Israel, home to peoples of different cultures and faiths, using unique

examples from the museum's collection of Holy Land archaeology, the foremost

holding in the world.

Highlights on view include Pilate Stone, "House of David" inscription (9th

century BCE), a comparative display of two shrines (8th–7th century BCE); the

Heliodorus Stele (178 BCE), royal Herodian bathhouse (1st century BCE);

Hadrian's Triumph: inscription from a triumphal arch (136 CE), the Mosaic of

Rehob (3rd century CE) and gold-glass bases from the Roman catacombs (4th

century CE); and the Ossuary of Jesus son of Joseph.[9]

|

Anthropoid Clay Coffins.

The anthropoid ceramic coffins of the Late Bronze Age Levant are a

unique burial practice that is a synthesis of Egyptian and Near Eastern

ideologies.

-

The coffins date from the 14th to 10th centuries BCE and have been

found at Deir el-Balah, Beth Shean, Lachish, Tell el-Far’ah, Sahab,

and most recently in the Jezreel Valley in 2013.

-

The coffins show Egyptian influence in the Ancient Near East and

exhibit many Egyptian qualities in the depictions on the face masks on

the lids.

-

See more at

Anthropoid ceramic coffins - Wikipedia.

|

|

Horned Altar.

One of the most significant discoveries at Tel Beer-sheba is that of a

horned altar, the first ever unearthed in Israel.

|

|

Tree of Life Goddess.

This 7,500 year-old goddess figurine from Neve Yam is among the world’s

earliest evidence for established religion, the origins of which date

back to the agricultural revolution, around 10,000 years ago.

-

It is similar to contemporaneous figurines, especially the one

discovered at Hagosherim, some 100 km away.

-

The striking resemblance between the two objects indicates that the

cult of the goddess was widespread by this time.

-

In later periods, the combination of a plant motif (the Tree of Life)

with the image of a woman (the goddess) became a common image

throughout the Ancient Near East, where it represented the goddess

Asherah.

-

See more at

Asherah - Wikipedia.

|

|

Carved stone masks.

These carved stone masks representing a human face belong to a rare

group of masks from the Neolithic period that were discovered in and

around the Judean Desert and are considered the oldest masks in the

world.

-

Based on the similarity with the plastered and decorated skulls that

appeared in sites from the same period, scholars assume that the masks

represented the spirits of the dead and were used in religious-social

ceremonies, such as ancestor worship, and in magic rites related to

healing and divination.

|

|

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A.

Statue (right). Gilgal. Limestone. L: 36 cm; W: 17 cm. Accession number:

K10343.

|

|

Pottery Neolithic.

Pebble figurine (left). Shaar HaGolan. Limestone. H: 22 cm; W: 10 cm.

IAA: 1979-493.

|

|

Figurine (center).

Figurine. Kabri. Late Neolithic. Bone. H: 4 cm; W: 1.5 cm. IAA:

1956-915.

|

|

Birth of the gods.

«Gods - beings that dominate the natural world and human activity -

appeared some 8.000 years ago in conjunction with the emergence of

agricultural communities, which had learnd to control their physical

environment and exploit its resources. The cult of these communities

centered around a female goddess identified with the earth; the training

of and caring for animals; and abundance and fertility. The male god,

represented by both human and animal figurines, is thought to have been

the goddess's spouse or son.»

|

|

The male god.

Male figurine (left). Beersheba. Chalcolithic period, 4500–3500 BCE.

Ivory. H: 33; W: 5.3. IAA: 1958-579.

|

|

The goddess.

Violin-shaped female figurines (left). Gilat. Chalcolithic period,

4500–3500 BCE. Stone. H: 17–22; W: 7.6–12.2 cm. IAA: 1992-1211,

1975-1032, 1992-1212.

|

|

The En Gedi temple.

The Chalcolithic Temple of Ein Gedi is a Ghassulian public building

dating from about 3500 BCE. It lies on a scarp above the oasis of Ein

Gedi, on the western shore of the Dead Sea, within modern-day Israel.

-

The temple was discovered in 1956 by Yohanan Aharoni during an

archaeological survey of the Ein Gedi region.

-

The excavations at the temple have unearthed a compound consisting of

a main building on the north, a smaller one in the east, and a small

circular structure, 3 metres (9.8 ft) in diameter and probably serving

some cultic purpose, in the center.

-

See more at

Chalcolithic Temple of Ein Gedi - Wikipedia.

|

|

Chalcolithic burial Cave in Peki'in in the Upper Galilee.

The cave is narrow 17 m long and 7 m wide with three different levels.

-

It contained many finding including Ossuaries decorated with human

faces. Dated 4,500-3,500 BCE.

|

|

Ossuaries and Incense Burners.

Pottery Ossuaries and Incense Burners, 4500-3500 BC.

|

|

Religion and ritual.

Figurine of a worshiper (center). Tel Jarmuth. Early Bronze Age,

2650–2300 BCE. Pottery. H: 2 cm. IAA: 1988-145.

|

|

Ritual objects.

Wall bracket for a lighting implement or incense burner, decorated with

a bull in relief (top). Megiddo. Late Bronze Age, 13th century BCE.

Pottery. H: 45; W: 14 cm. IAA: 1937-876.

|

|

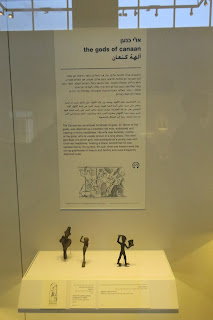

The gods of Canaan.

Figurine of the storm god (right). Megiddo. Late Bronze Age, 15th–13th

century BCE. Bronze. H: 13 cm. IAA: M-1083.

|

|

Shrine of the stelae.

A small shrine with a single room was unearthed in Hazor’s lower city.

|

|

Cultic objects from the Shrine of the Stelae.

Cultic objects from the Shrine of the Stelae. Hazor. Late Bronze Age,

15th–13th century BCE. Basalt.

-

In the wall opposite the entrance, there was a niche containing a row

of standing stones (masseboth), with an offering table and a figure

carrying a bowl in front. The crescent on the figure’s breast was a

symbol of the moon god Sin. The central stone features a pair of hands

venerating moon symbols. The stones, as well as the ones found outside

the temple, were commemorative, perhaps recalling a king, priest, or

ancestors.

-

The lion relief on the right belongs to an earlier phase of the

shrine.

|

|

The Israelites.

Bowl decorated with animal figures (left). Tell el-Hammah. Iron Age II,

10th century BCE. Pottery. Accession number: K11174.

|

|

Model shrine.

Model shrine. Trans-Jordan. Iron Age II, 9th–8th century BCE. Pottery.

H: 23.5; W:18; L: 21 cm. IAA: 1940-286.

-

Models of this type reflect actual temple architecture. Their capitals

and columns closely resemble some of the architectural elements found

in the excaation. The function of the models, however, is not clear.

-

The dove portrayed on this object probably represents the goddess

Asherah. The models recall the biblical description of the entrance to

Solomon’s Temple, with its pair of free-standing columns, “Yakhin” and

“Boaz.”

|

|

Model shrine.

Model shrine. Trans-Jordan. Iron Age II, 9th–8th century BCE. Pottery.

H: 29; W: 30 cm. Accession number: 82.24.415.

|

|

Edomite clay stands from Hazeva.

Ritual stand decorated with animal figures (center left). Hazeva. Iron

Age II, late 7th – early 6th century BCE. Pottery. H: 53; Diam: 23 cm.

IAA: 1995-101.

|

|

Holy of Holies from the sanctuary at Arad.

Holy of Holies from the sanctuary at Arad. Iron Age II, 8th century BCE.

Limestone. IAA: 1967-1401, 1967-1402, 1967-1403.

-

A small sanctuary was uncovered in the Arad fortress on Judah’s

southern border. It is the only Judahite temple ever discovered.

-

Like most Ancient Near Eastern shrines, including the Temple in

Jerusalem, it was composed of several spaces reflecting a hierarchy of

sanctity.

-

Deep inside was the Holy of Holies, with a smooth standing stone

(biblical massebah), possibly signifying God’s presence, and two

altars still bearing the remains of the last incense offered there.

-

The sanctuary was intentionally buried in the time of King Hezekiah,

who sought to abolish all public worship outside the Temple in

Jerusalem.

|

|

The Arameans.

Cultic stele. Bethsaida. Iron Age II, 9th–8th century BCE. Basalt. H:

115; W: 59; D: 31 cm. IAA: 1997-3451/980.

-

The Arameans comprised a number of kingdoms based north of Israel. The

most prominent of these was Aram-Damascus, portrayed in the Bible as

Israel’s bitter enemy.

-

This carved stone slab was discovered in the capital of the Aramean

kingdom of Geshur, near the city gate. The bull-headed figure wearing

a sword probably symbolized either the chief god Hadad, who was the

storm god responsible for rainfall, or the moon god, who was

responsible for the swelling of the rivers. Alternatively, it may have

represented a fusion of the two.

|

|

Iron Age II.

8th–6th century BCE.

-

Figurine of a potter (left). Akhzib. Iron Age II, 8th–6th century BCE.

Pottery. H: 12; W: 5; L: 5 cm. IAA: 1944-58.

-

Model shrine (center). Akhzib. Iron Age II, 8th–6th century BCE.

Pottery. H: 17; L: 8.8 cm. IAA: 1944-46.

-

Figurine of woman bringing offering (right). Akhzib. Iron Age II,

8th–6th century BCE. Pottery. H: 18; Diam: 6 cm. IAA: 1961-563.

-

Figurine of woman bringing offering (far right). Akhzib. Iron Age II,

8th–6th century BCE. Pottery. H: 19; Diam: 5 cm. IAA: 1944-50.

|

|

Mold for Making Masks, Special Display.

Archaeologist Michaël Jasmin explains to us the importance of his

discovery of this mold for making masks in the Phoenician town of

Achzib.

-

This mold, the only one of its kind known to date, was recently

discovered on the floor of a cultic building in the Phoenician town of

Achzib.

-

It was used for the mass-production of pottery masks depicting male

faces. Masks of this type have been found mainly in Phoenician tombs

throughout the Mediterranean.

-

Too small to have been worn on the face, they may have been hung on

the tomb walls, on wooden statues, or on coffins to drive out demons

and evil spirits.

-

The Special Display includes masks found in graves in Achzib. Almost

all were produced in molds like this one.

|

|

Head of Athena.

Head of Athena, found in Tel Naharon (northern Beth Shean), 2nd century

AD. Marble from the island of Thassos in the Aegean Sea. H: 64; W: 38.

IAA: 1978-505.

-

On 5 October 2023, a 40-year old Jewish-American tourist was arrested

at the museum after hurling a marble head of the Greek goddess Athena

and a statue of a griffin grasping the wheel of fate of the Roman god

Nemesis into the floor, shattering the latter artefact.

-

Police described him as a radical who considered the artefacts “to be

idolatrous and contrary to the Torah”, while his lawyer claimed he was

suffering from Jerusalem syndrome.

-

The damaged artefacts, both of which dated from the Second Century AD,

were placed under restoration.

|

|

Reconstruction of a church bema (presbytery).

Reconstruction of a church bema (presbytery). 4th–6th century CE.

H: 520; W: 940; D: 740 cm. Bequest of Dan Barag, Jerusalem.

-

The church bema reconstructed here comprises original

architectural elements excavated at 17 different sites. The pieces fit

together perfectly, as if they came from the same building.

|

|

Reconstruction of the Susiya synagogue bema (podium).

Reconstruction of the Susiya synagogue bema (podium). Southern

Hebron Hills. 5th–8th century CE. Marble. W: 490; D: 290 cm.

-

The magnificent synagogue of Susiya in the southern Hebron hills stood

for hundreds of years and underwent many renovations. Its

bema (podium) was built next to the long northern wall, which

featured three arched niches. The central one likely held the Torah

Ark, and the two others each held a menorah. The bema’s carved

and incised motifs included menorahs, animals, and plants. Numerous

donor inscriptions on the walls and floor attest to the community’s

active participation in the building’s construction.

-

The posts, chancel screens, carved decorations, menorah, and floor

panels exhibited here were all found in excavations of the Susiya

synagogue. The human and animal images that originally decorated the

synagogue were defaced in the 8th century, when figurative art was

prohibited under Muslim rule.

-

Synagogue floor (bottom). Beth Shean synagogue. 5th–7th century CE.

Stone. H: 276; W: 435 cm. IAA: 1963-934/1-3.

|

See also

Sources

Location